A master plan provides a conceptual layout to guide the future development of a school’s physical facilities in keeping with its mission and goals. The effectiveness of the master plan determines the success of the institution’s future design and construction efforts. A well-conceived master plan can inspire and rejuvenate a school community and propel it forward confidently into the future.

Creating a successful master plan that remains relevant over the long-term calls for a thoughtful and thorough process. This article highlights essential aspects of the master planning process in two parts: Part 1 outlines some critical steps that apply to all master plans, including clarifying frequently encountered misconceptions. Part 2 delves deeper into the specific challenges associated with historic buildings.

While the article specifically addresses schools in urban contexts, much of what is discussed is generally applicable across a wider cross-section of campuses.

Where do we begin?

1. Establish a clear goal:

A strategic plan answers the question “where do we want to go?” while a master plan provides a road map that shows how we can get there. In identifying a clear goal for the master plan, always begin with the school’s strategic plan. Understand your primary reason for undertaking the plan. Define the overall parameters and a schedule for completion. Is there a specific institutional milestone or date by which the plan needs to be put into action? Clearly articulating and communicating the goals and priorities of the plan at the outset ensures a focused and streamlined process.

2. Set the stage for success:

Who are the decision-makers? Assemble a school leadership team, often comprised of administrative and academic personnel as well as school trustees with experience in development or construction. Diversifying the experience of your team will serve to guard against overlooking basic considerations during the process. Undertaking a master plan can be intimidating and identifying an architecture firm with a proven track record to guide the school through the process is a crucial step.

3. Master Planning is about People:

A common fallacy is that master planning is about physical space. A school is defined by its culture, which in turn is informed by its traditions and values and sustained by the school community — the people who make up the community. This is what gives each school its individual identity and personality. The values and culture of the school should serve as fundamental drivers that help to guide the master plan.

4. A Non-linear Progression:

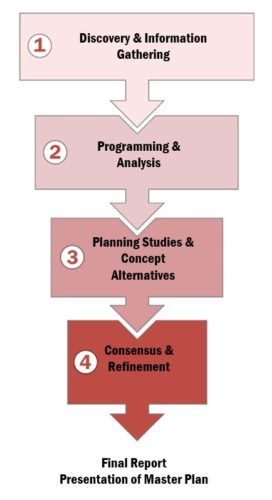

In concept, development of a master plan follows a logical sequence of steps as represented by the first diagram. It begins with Information Gathering, then progresses from Programming, where the scope of the plan is defined, to Concept Design, where several alternate approaches are explored, and culminates in Consensus and Refinement, where the design direction is agreed upon and advanced. The entire effort is documented in a comprehensive final report.

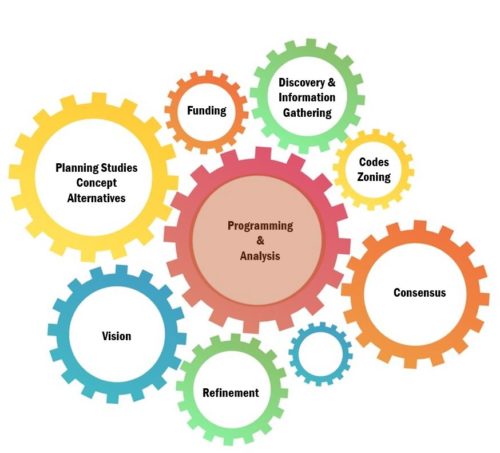

In reality, master plan development is much more akin to the second diagram: an interlinked array of gears in differing sizes, moving at different speeds, each continually informing the other. It is an iterative process, with discussions occurring simultaneously in several forums, and decisions being continually revised as more information and alternate considerations emerge. For example, information gathering often occurs simultaneously with programming. Budgets based on a preferred design idea may prove infeasible and require revisiting earlier assumptions.

5. Inclusive Process:

Programming is the most important step in creating a master plan because it defines the problems to be solved and the scope of the plan. A key aspect of this is identifying the constituents who will participate in the programming interviews and discussions. An inclusive process to build consensus around future changes is crucial for the success of the master plan. Besides faculty, administrators, operations and maintenance staff, be sure to include students and parents. With younger student populations, a more creative approach involving drawings or interactive tools can serve as an effective way to gather their input in lieu of a question-answer format. Is the school used by the larger community after hours or on weekends? Garnering broader feedback could provide valuable insights for program definition, as well as help to ensure community support for the plan.

Interviews are only as useful as the questions that are asked. Spend time with your architect to ensure that targeted questions are being asked.

6. A Litmus Test for Proposed Changes

by PBDW Architects

To be relevant, a master plan requires the validation and consensus of its stakeholders During every phase of the process, particularly during programming and conceptual design, there will be differing opinions and conflicting requirements. This is an inevitable product of any democratic process. How can we reach consensus? The single most important thing to keep in mind throughout the process is the school’s mission. At every fork in the road, ask: Does the plan reflect the vision laid out in the school’s strategic plan?

7. Interdependence of Budgets and Phasing:

Master plans are rarely executed in one phase. Often, construction is spread out over several years and phases, especially when occupied buildings are involved. Understand what resources will be necessary to effectively realize the proposed plan and whether projected costs are within the institution’s financial capacity. Will fundraising thresholds align with scheduled phasing? Unrealistic plans may never be executed and can lead to unnecessarily wasted time and effort. Exercise prudence and use conservative estimates with contingencies early in the process to buffer against the inevitable unforeseeable costs down the road.

8. Future Proofing:

A successful master plan allows for unforeseen future needs through an adaptable layout and the growth potential of infrastructure systems. Questions to consider: How will these spaces work in 10-15-20 years? Are they flexible enough to be easily adapted to evolving needs?

9. Living Document:

Another misconception is that master planning is a finite process. The reality is that a master plan continues to evolve over the years as an institution’s needs develop and society changes. Rather than a static document, it is an evolving resource that needs to be revisited and updated at appropriate intervals.

10. Stay the Course:

Finally, do not short circuit the process. There are many things that can go wrong. It is not uncommon for the process to be drawn out or derailed by side projects, lack of consensus, change of leadership or the innumerable daily challenges that educational institutions face. Resist the temptation to go for the “quick fix” or “bandaid” solution. In the long term, this will not only result in wasted time and money but worse, will limit future possibilities and preclude the maximization of potential.

Master plans take patience, determination, and much hard work. However, they are sound investments that can pay back huge dividends in the clarity of purpose that they provide for guiding the well-informed allocation of future resources.