There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to classrooms. In most schools, classrooms vary widely in terms of their size, shape and programmatic functions. They tend to be buzzing hubs of activity, packed beyond their intended capacity with students and teachers, who at various times may move around the room, sit shoulder-to-shoulder working quietly or huddle together in groups to collaborate on projects. Throughout the course of a school day, desks and chairs may be frequently rearranged to accommodate the learning taking place within.

Reopening schools in a post-Covid-19 context requires not just that we find ways to adapt our existing classrooms to accommodate new safety concerns, but that we continue to facilitate communication and flexibility in our learning spaces. While this will be challenging, the fact that most of the furniture within schools is movable opens up a variety of possible solutions that can be used at different times within a space.

The classroom adaptations described here can be broadly divided into two categories: Physically Distanced Configurations, and Physical Divider Configurations.

Each is intended to accommodate all learners, work within the limits of existing facilities, be reversible, continue to facilitate communication, and allow for flexibility in learning spaces.

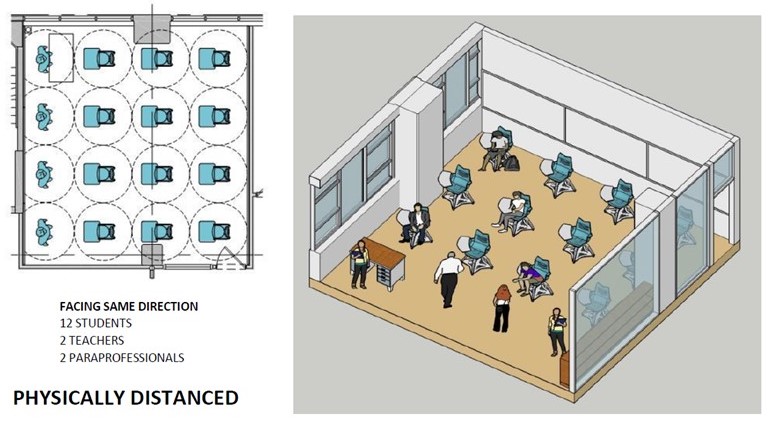

Physically Distanced Configurations

The main benefit of the Physically Distanced strategy is that it increases the distance between occupants, which is preferred by the CDC over other virus mitigating strategies. The spacing of furniture creates clear paths of circulation for teachers or other support staff in classrooms. With limited physical modifications needed for furniture, this strategy is easy to implement and has a negligible cost impact for retrofits. The simplest version of this configuration is to organize desks in straight rows and columns. More desks could be accommodated in a given space if the desks were arranged in a checkerboard pattern. The trade-off in this case is the resulting zig-zag circulation between desks. Multiple furniture layouts could be marked on the floor with tape in various colors, allowing for the easy rearrangement of desks to accommodate a variety of learning activities while ensuring that appropriate distances are maintained between learners. However, this strategy will be the most limiting in terms of the number of people per classroom.

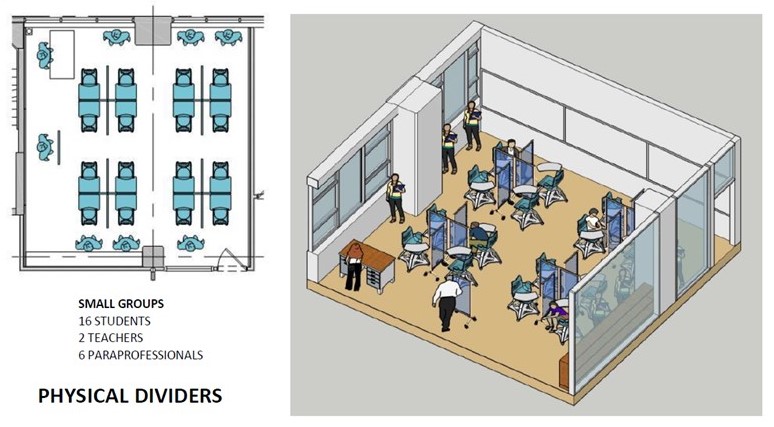

Physical Divider Configurations

With the introduction of transparent screens between people, the Physical Divider strategy explores decreasing the distance between occupants while still maintaining physical separations to limit the spread of viruses. This approach accommodates more students and teachers per classroom than physical distancing. It allows students to work more directly alongside other students, teachers, or support staff including paraprofessionals. The dividers could be temporary physical modifications to furniture or could be mobile freestanding units that can be moved around as needed. These modifications are easy to implement, but there are cost, procurement, and maintenance implications that must be considered.

With either of these two classroom strategies, CDC guidelines for PPE should be followed by both teachers and students.

Compensating for Loss of Density

Since both of these adaptations result in fewer students per classroom, other means to increase capacity will need to be explored. Operational adjustments such as staggered schedules, with some students remotely logging in to class while others are physically present, can effectively expand the reach and utility of classrooms that now hold fewer students. Repurposing or modifying the architecture of existing spaces can create larger and more flexible spaces for learning. For example, replacing a common wall between adjacent classrooms with a movable partition would allow for larger class sizes without increasing the number of faculty. Auxiliary spaces such as cafeterias or gyms can be converted into provisional classrooms using temporary partitions. Open-plan, collaborative spaces can be enclosed to create acoustically functional instructional areas.

Supplemental Strategies

Recognizing that spatial adjustments alone are insufficient as safety measures in any space, a combination of other strategies should be considered to address indoor air quality, door operations and circulation. Door hardware can be modified to minimize the need to touch handles, by adding foot-pulls, for example. Smart building technologies might include automatic operators at high traffic doors. Hands-free technology can be added to plumbing fixtures and soap dispensers in restrooms. Existing air filters can be replaced with MERV 13 or HEPA rated filters, and systems can be run longer to flush rooms when they are not in use.

It is unreasonable to expect students to remain in the same classroom day after day without some relief.

Minimizing movement within a school reduces cross-exposure between students and surfaces. Cohorts of students could remain in their classrooms while teachers move between classrooms to teach the different subject areas. Boxed or pre-packed lunches can be eaten in classrooms to avoid larger group gatherings in cafeterias.

It is unreasonable to expect students to remain in the same classroom day after day without some relief. Within the overall framework of physical distancing, avenues to provide some spatial variety should be explored. Continuing some form of non-contact physical education in the gym, holding classes outdoors when weather permits and possibly shortening the school day are some options. Another possibility is to allocate available enrichment spaces exclusively to a single classroom for one full or half day each week, on a rotating basis. For example, in a school with 30 classrooms and three common spaces—a cafeteria, a library and an art room—each class could relocate to one of those common spaces for half a day every five days or a full day every ten days. Of course, if the half day model is used, common spaces would need to be cleaned during the day before being occupied by the next group of students.

While it is more feasible for elementary and middle school students to remain in the same classroom through the day, this strategy becomes more complicated in high schools, where students typically have individualized schedules based on their choice of core courses and electives. A different approach will be required here, informed by the strategies outlined above. Cohorts might include a greater number of students who share the same live core classes but use online learning for electives.

Adapting to these new conditions together will be a “teaching moment” whose lessons will likely extend far beyond the school building.

Reactivating our classrooms in a pre-vaccine COVID environment will require establishing a new level of trust within the school community, to overcome fears about spreading the virus. Building this trust starts with employing recommended protective measures in a visible way, while maintaining a high-quality learning environment. As we have done in our homes and communities through the pandemic thus far, parents, students, and faculty will face a common learning curve in this new school landscape. Adapting to these new conditions together will be a “teaching moment” whose lessons will likely extend far beyond the school building.

A more detailed look at options for Physically Distanced classroom configurations can be found here.