While the pandemic has upended everything, the crisis provides an opportunity to look at existing challenges with fresh eyes. For higher education, that likely means campuses that are flexibly focused on what is sustainable.

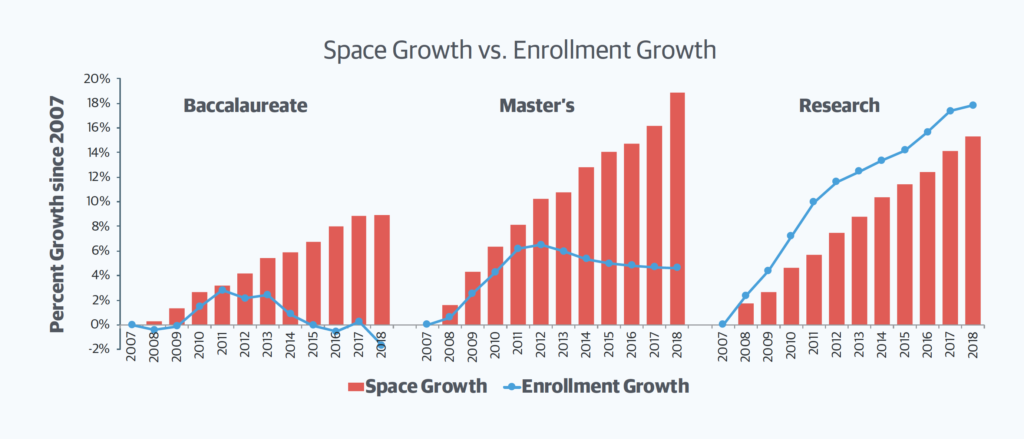

Entering 2020, several truths enumerated in Gordian’s State of Facilities in Higher Education report were clear. Campuses have continued growing (8.5% – 19% based on institution type) faster than their enrollment alone could sustain financially.

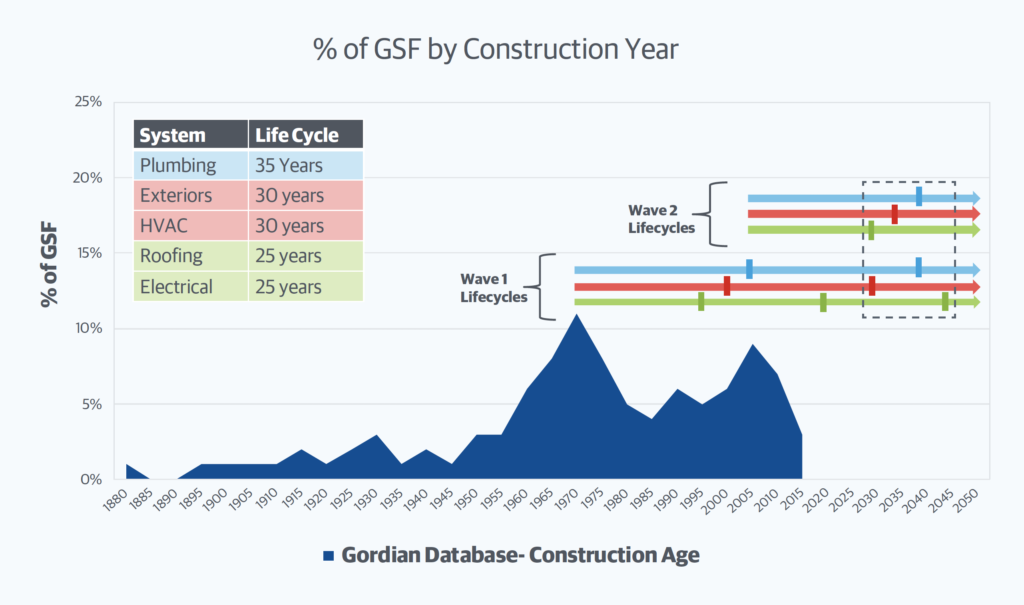

Historic waves of construction were presenting an impending crisis as building system life cycles — the predictable need to renew and upgrade roofs, HVAC and other systems — were all coming due simultaneously for huge swaths of the campus.

And campuses, in total, were overbuilt in light of the demographic decline coming in the middle of this decade. An “urgent” problem facing schools would arrive in about the same time it takes a single cohort to graduate. And then the pandemic stormed the globe.

Urgency has now been reframed. Higher education institutions were forced to act swiftly to protect their communities. Classrooms became virtual, sports were canceled, research curtailed, critical rituals like commencements and reunions indefinitely deferred, many summer programs cancelled, endowments and state funding threatened, and everyone was struggling to understand how to plan for the fall and beyond. While the country is attempting to rebound, the future remains highly uncertain. But one fact is clear: the pre-COVID truths facing campus facilities have been amplified and accelerated — making a bad situation much worse for many institutions.

In the very short term, having a little extra space may ease social distancing. But space is expensive. Revenue is in jeopardy and a large campus footprint is looking harder to afford. Campuses that were oversized for a shrinking pool in five years may very well be unsustainable as soon as September.

As leaders look for cash to keep the doors open it is tempting to curtail capital investment. And in some cases that may be wise. But those impending life cycles are not going away, and institutional survival relies on functioning roofs, HVAC and electrical systems, and overall structural integrity tomorrow, five years from now and in perpetuity. Neglect increases costs just when the financial future is most uncertain. So higher education faces its own “curve” that it must flatten: preventing a spike that will overwhelm facilities condition and capacity.

What We Know Now

Every school leadership team is facing extraordinary decisions in the near term about their institutional future. Three things learned already from the pandemic can be applied to campus challenges looking forward:

- Action is possible with great impetus.

- Each campus decision has facilities implications.

- Facilities realities powerfully affect the strategies available for success.

Exploring each offers insights for moving forward.

Taking Action. Notoriously cautious about change, academic communities implemented a new way of doing business almost overnight under the threat of the coronavirus. The question now is whether schools will adopt this as a new operating mindset or see it simply as a necessary pain to be endured before returning to life as usual? Can they adapt their decision making frameworks to address the unfolding threat to the very fabric of their campuses with the same clarity as they saw the threat to the personal safety of employees and students? The answers lie in part on how well institutions organize their analysis and planning within decision-making frameworks. A strong planning approach promotes shared understanding of the choices the community faces, and a shared rationale for action.

Facilities Implications. Strategic choices must be carefully grounded in reality. Too often, programs and services plans fail to consider facilities demands — capital, space, operations —resulting in costly, counterproductive surprises later. The new realities of resource constraints and heightened competition demand clear and timely incorporation of facilities perspectives and realities into institutional planning. Campuses of today were built with the growth and density business models of the last century as their guide. What new design principles must we embrace?

Facilities Realities. Much of what is possible — programmatically, financially, and operationally — is defined by current physical assets and commitments. What programs can commence/grow without taking on new facilities costs? What assets are “locked in” because of debt service or other considerations? What strategies are possible for re-use, de-accessioning, or monetizing assets with relatively low future value? Previously expanding campuses find themselves with limited financial flexibility or liquidity as they confront extremely difficult financial futures. Assumptions about asset value, including the ability to unload real estate portfolio elements, must be revisited. Addressing these questions reveals a starting point for what is possible; a foundation for planning to weather the long, turbulent times ahead even as short-term recovery decisions are being made.

What to Do

In the midst of planning to re-populate a campus for this fall, looking forward beyond December — let alone 2025 — may seem impossible. But failing to seize this opportunity risks not only missing a singular moment to correct course, but also jeopardizing the future of the organization. Given the significant time and effort it takes to alter campus facilities and the very long life of such assets, quick decisions made today will reverberate for a very long time. Two strategies seem essential:

The Reality Check: Do existing campus plans still make sense?

The pandemic and its repercussions may be blowing off course existing campus facilities plans. Priority No. 1 is probing for weaknesses:

- Gaps and flaws now exposed by enrollment, operational or financial concerns.

- Important facilities challenges that are not yet incorporated.

- Elements of the planned campus footprint that are longer required going forward.

- Aspects of the plan that cannot be easily modified.

Fighting to get back on course before assessing whether that course now makes sense is unwise and risky. If the current plans don’t bode well for the enrollment and financial challenges being faced today, they will surely fail when the demographics cliff arrives.

The Diagnostic Check

Can today’s campus respond to tomorrow’s needs/demands?

It is already clear – the campus of January 2020 is not the campus necessary to support the educational enterprise in September 2020. Understanding what your campus and its facilities organization are set up to do today is critical to effectively inform the plan for tomorrow. It is essential to:

- Determine what your facilities organization is actually set up to do. Compare that with what your community needs going forward.

- Identify what assets can be flexibly repurposed.

- Focus your limited resources to minimize risk, support programs and sustain cash reserves.

- Set realistic facilities expenditures and plan to live within that framework now.

- Build community awareness of the risks that come with not changing.

Plans informed by the real capacity and capabilities of current facilities produce better decisions and make it possible to act strategically even in the midst of unprecedented change.

Faced with an unprecedented set of challenges, higher education institutions require innovative solutions. Leaders must heed the glaring realities and answer the call to action. They must not miss this opportunity to take stock of where campus facilities and facilities plans are today and align them with a re-imagined university, one that will not only react to the pandemic today but the educational community and realities of the future.