(This is Part 1 of a 2-part series the embarks on The Learning Brain and the Discovery to optimize learning customization and engagement for each Student)

- What if we could better understand what goes inside students’ heads, literally, while they undergo learning experiences and environments?

- What if we could truly know when students achieve peak performance, when their engagement is at its highest, and when their interest is maximized? What were they doing? What happened in those moments?

- What if we could ‘see’ what they are sensing and feeling? And what if we could use that information to design better and more sensible learning environments?

This provocation begins to address these questions. We do not have to wait anymore to find answers. Our focus is to find links between Neuroscience, Learning and Learning Environments. Only through understanding how each of us best learns, can we customize an educational experience to every single student. Our Educational systems are designed for the Average. Students are grouped together depending on their birthdate and given content to digest broken per disciplines, 1 hour at a time. Although there are attempts at differentiation, and some of them are fairly successful, we still have no idea if students are truly engaged, interested, and excited by what they are doing.

We understand that true engagement occurs when students lose the sense of time, when they interact with a project or an idea to reach the ‘Flow’ as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls it in his book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Through interactions with administrators in various international independent schools reaching high levels of engagement is a key goal for schools. Quoting Fiona Reynolds, Deputy Head at the American School in Mumbai, “Engagement is the name of the game in education.” This provocation shares instances and moments when engagement hit high levels while students were observed.

This provocation is presented in two parts: first we introduce a brief summary of what we now know, from a strong body of research about neuroscience and learning as it relates to learning space; in part two, we will share what we have recently discovered through our primary research: The Brainware Research Project where we set off to learn what, how and when are students most engaged and interested at school.

WHAT WE NOW KNOW

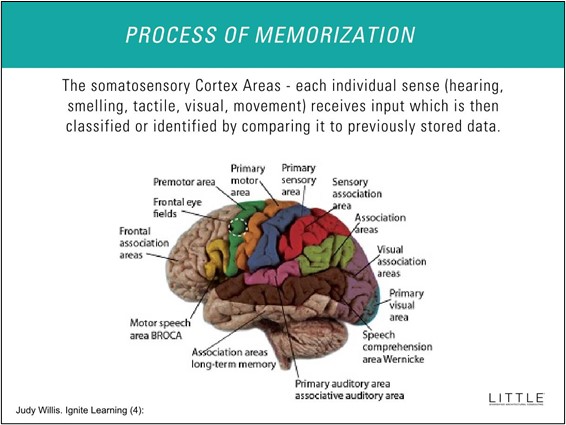

Over the last 10 to 15 years, we have learned many lessons through neuroscientific research about the learning brain. These lessons have taught us the importance of Somatosensory learning experiences in making learning memorable. As Judy Willis states in her book Ignite Learning, when content is presented with multiple senses in mind, more of that learning experience is ‘archived’ in the various sensorial zones of the brain hence creating more dendrite pathways between the various zones and making the recollection of that ‘knowledge’ more engrained (4). This is the reason why hands-on experiences are always much better learning experiences than passive experiences (reading content or seeing a slide presentation about a topic). A great example is learning about a car by reading and seeing images, vs riding on one, seeing it, smelling it, feeling it, hearing the engine….): they create more memories associated with more areas of the brain where they are stored and hence connections created.

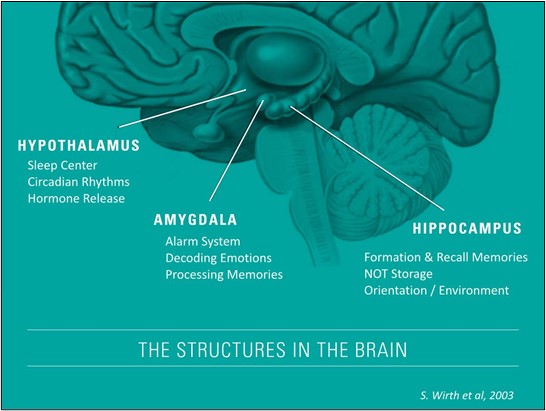

We have also learned that when the amygdala, the alarm structure in our brains that decodes emotions and processes memories, is shut down (due to stress, fear, nervousness, strain,… situations created by serious problems at home, or fear of bullying, or strain from lack of confidence about an exam) it is virtually impossible to process new content and memorize new learning. (S. Wirth 2003). Relaxing the Amygdala can be achieved in multiple ways, through meditation, breathing or even Music. At Invest Collegiate Charter School in Charlotte NC, all students start their day with a communal song, a way to cross a ‘threshold’ from the worries outside of school to the new day of learning. Small things can make a Big impact.

A third element of Brain-based Learning that we now know is that Wellness is critical to the Learning process. Within Wellness 4 aspects are very important to the learning process: Biophilia, Sleep, Attention Restoration, and Movement. This provocation will encourage schools to rethink their learning experiences based on these 4 concepts.

First, our brains need to feel connected to nature. Any biophilic learning environment that enhance daylighting, connections to nature and sun via views, and even bringing natural materials into the spaces will facilitate a better environment for our learning brains. Another idea is to be able to push the learning experience outdoors.

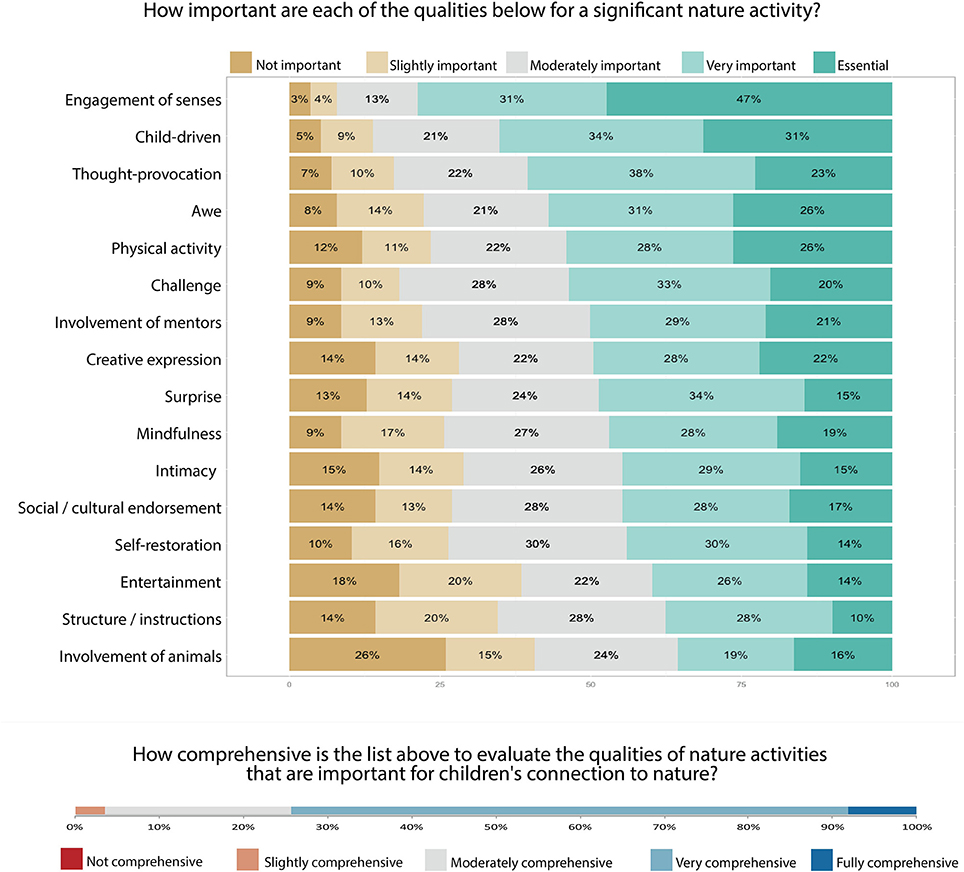

In the article “A Framework to Assess Where and How Children Connect to Nature”, Giusti, Svane, Raymond and Beery assess that connecting and being outside has very important implications to how students engage with all senses (demonstrated to increase learning), support thought-provoking experiences, enhance self-driven learning, and enhance mindfulness among many other benefits. See table below:

Second, there has been so much research over the last few years demonstrating the importance of Sleep. Why is sleep so important? Through sleep we turn short term memories into long term ones. Sleep cleans toxins from our brains, it regulates our mood and strengthens our immune system. Schools and parents ought to develop stronger scheduling patterns that allow students better sleep and hence better health and learning.

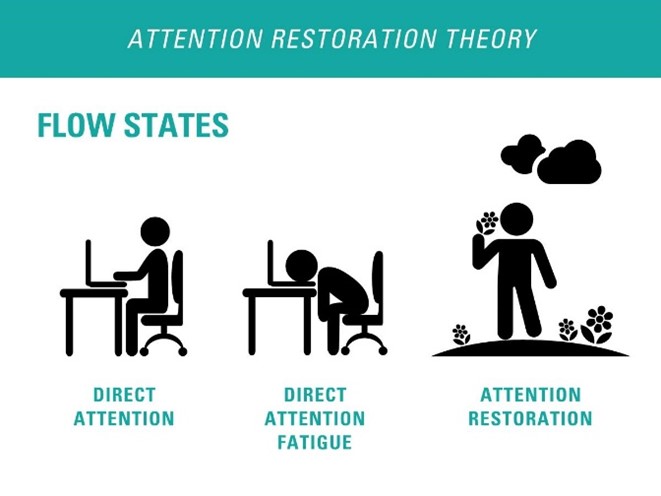

Third, Attention Restoration is a lesser know and understood problem but very real, nonetheless. According to one of the prominent researchers of the Learning Brain, Dr. Sousa, our adult brains have a maximum attention span of 7 minutes before we start drifting off and losing our focus. For kids its even less. After a serious attention session, we enter attention fatigue where we may be listening, but we are not retaining information. We need to undergo an attention restoration session. That could be a small ‘mental brake’ away from the activity (or class or lecture), by going to a different room away from the noise, or stepping outside to get fresh air, or look out of a window at a tree, clouds or sky. Our learning environments need to provide these opportunities to ‘restore’ our brains so we can be ready for the next session. But scheduling at schools also need to provide moments and space for restoration to happen.

Fourth is Movement. Learning experiences that allow students to move and chose the spaces they want to learn in have a dual benefit. Physiologically, it is proven that movement facilitates the flow of blood into our brains therefore supporting better learning. Psychologically, it supports students’ agency and a sense of ownership of how, where and when they will learn.

It is our responsibility as designers to incorporate the latest research in Brain Science in the way we discuss educational experiences in the projects we do with our clients and how we design learning environments. Understanding that each student is different and each one requires a different strategy to facilitate an optimal learning experience is imperative to their success.

In Part 2, we will share primary research conducted at a school where we get “inside” students’ brains using Brainware Technology to see what happens to their emotions (Engagement, Interest, Stress, Focus, Excitement and Relaxation) as they experience various typical learning ‘moments’ such as lecture format, test taking, group work and Lab work.

REFERENCES:

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. FLOW The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial; Edition 2008.

- Giusti M., Svane U., Raymond C., and Beery T. (2018) “A Framework to Assess Where and How Children Connect to Nature”, Frontiers in Psychology.

- Sousa, David A. How the Brain Learns, Fourth Edition. Corwin. 2011

- Willis, Judy. Research-based Strategies to Ignite Student Learning. ASCD. 2006.

- Wirth S., Yanike M., Frank L. M., Smith A. C., Brown E. N., Suzuki W. A. (2003) Single neurons in the monkey hippocampus and learning of new associations. Science 300: 1578-1581.