The good news – we as a group of educators and designers together – can combine our expertise and create access to opportunities for all students – by applying what we know from research.

Introduction

As the impact of school design on child and adolescent health and development continues to be of growing interest, evidence-based frameworks are needed to advance new ideas for practitioners advancing rich learning experiences to support all students in their total well-being. What we are coming to understand about the complex interconnections between environment, health, and learning can be translated into new cross-cutting initiatives in education to surround students with wide-ranging resources and opportunities. What happens when best practices in therapeutic design and research converge with innovative approaches to learning? Students get to inhabit enriched spaces and their learning process interact with a powerful sense of well-being through shared social values, while teachers increase their opportunities to engage every student more deeply.

A therapeutic lens for learning casts new light on the role schools can play in a much broader context of human-environment relationships by integrating what we know from other fields of research to serve students at their highest level of total well-being (Kaplan 1995). As a follow-up to our EDspaces 2020 session, this article captures key research insights for student well-being and highlights four attributes of restorative environments that can be applied to therapeutic settings to actively promote healthy development.

Therapeutic Lens for Learning – Four Attributes

“Stress” can be defined as the condition that results when person-environment transactions lead the individual to perceive a discrepancy (whether real or not) between the demands of a situation and the biological, psychological, or social resources of the individual (Evans, G.; Cohen, S. 1987). Through the salutary effect of viewing (and of being in) nature, the physical school environment can enhance positive emotion, and assist in the recovery of attention depletion and stress overload (Berto 2014). Incorporating attributes of therapeutic environments combined with nature’s benefits will help establish a sense of holistic well-being for students of all ages. How does nature deliver these benefits? It is posited that the ‘soft fascination of nature’ engages our involuntary attention and allows us to disengage from our everyday demands promoting psychological restoration (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989). Research has shown that restorative environments, whether it is a setting in nature or exposure to natural scenes, allows the renewal of personal adaptive resources to meet the demands of everyday life (Berto 2014).

The four attributes of a restorative school setting are: fascination, being away, extent, and compatibility. 1. Being away is any setting that offers the opportunity to escape from our everyday; (2) Extent has been variously defined as a) offering expansive spaces and contexts that allow us to find a “whole other world” with sufficient scope to engage the mind (Kaplan 1995); and b) referring to the need for cohesion and legibility in a physical setting (3) Compatibility provides a good “person-environment fit” (Kaplan, 1995) and facilitates activities that are “compatible” with our intrinsic goals and motivations (Kaplan, 1995); (4) Fascination arises from stimuli that are curious and engaging with sufficient interest to hold our attention effortlessly, but not so much to as to exclude room for reflection. Below we contextualize these attributes in a physical school setting.

Fascination

Fascination in learning spaces supports a need for learning experiences that effortlessly capture one’s unique attention, emotion, and imagination. While much of the school day is choreographed to a schedule, a design that incorporates a sense of curiosity and allows for emergent teaching and learning, is one that promotes restorative health benefits. A design that highlights the importance of fascination by designing with nature can be seen at the CCSD59 Early Childhood Learning Center in Mt. Prospect, Illinois. The courtyard gardens with meandering pathways through sustainable landscaping invites students to explore multisensory micro-spaces outdoors. Meandering pathways serve as an environmental cue indoors and outdoors to reinforce the pattern language of fascination as an invitation to ‘dive into’ learning with one’s whole self in both state-of-the-art spaces and natural environments. Strong visual and physical connections to the outdoor courtyards serve to bring nature and daylight in throughout the school day, prompting fascination to linger through changing sensory perceptions of flora and fauna.

Being Away

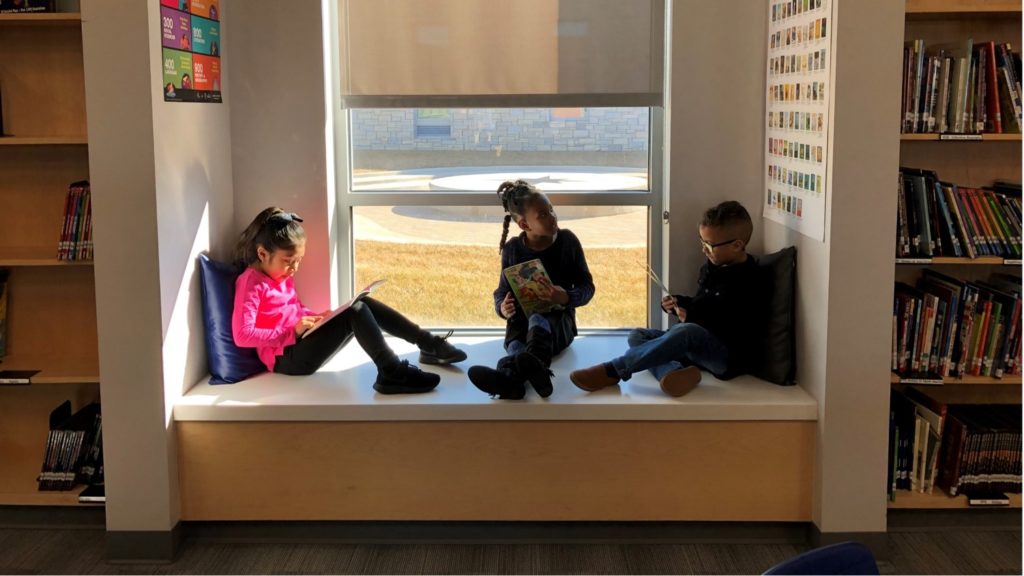

Being away in learning spaces offers each student a choice to inhabit smaller, more personal spaces. These moments of ‘microarchitecture’ promote restorative effects by providing an option to get away from habitual and predictable activities. Offering students opportunities to spend some down time in the school garden, a reading nook, or a favorite cozy space within a shared space, allows the ‘mind to wander’ for a reset. The importance of being away can be seen in the design of the Laraway School in Joliet, Illinois. The interweaving of intimate seating for 2-4 in cozy window nooks, outfitting the library with soft mobile furniture for intimate reconfiguration, and breaking down large spaces with threshold concepts like the ‘front porch’ – results in a holistic embrace of being away spaces designed to promote personal choice and comfort.

Extension in learning spaces opens opportunities to design for expansion (“a whole other world”) at the same time providing for coherence and legibility both indoors and outdoors. Extent matters at every scale of the building and grounds as a type of environmental wayfinding to promote cohesive connections between each element in an environment. The feeling of being able to move through the environment, look for the information it provides, and be immersed in the experience, acknowledges the need for a variety of stimulating enrichments with nature, color, light, textures, and signage. When learning spaces communicate the potential for personal interaction to enliven their flexibility, students get the chance to ‘read’ their school as anticipating their creative input and interpretation.

Each classroom at Crow Island School in Winnetka, Illinois exemplifies extent as the pedagogical heart of the school. Wide and tall corner windows extend a sense of the horizon, beyond the present-day interior world, built in bench storage are sized appropriately for young children, individual outdoor classroom courtyards nestled between classrooms for easy access, cohesive modular furniture to shift and move as needed, built in display and library cabinetry, self-healing pine wood walls for pin-up, work room, and amenities for personal care – child’s bathroom, sink, water fountain.

Compatibility

Enhanced demands on directed attention may be linked to attention fatigue (Kaplan 1995; Kaplan and Kaplan 1989). Attention-demanding tasks associated with school life typically follow standardized schedules and prescribed activities even for young children. The antidote to ‘on task’ is to take time out from attention-demanding tasks and spend time in natural environments that demand less cognitive resources and enable one to recover attentional capacities (Ohly 2016). Compatibility in learning spaces provides this effect by including time and environmental features to prompt engagement in activities that are “compatible” with the intrinsic motivations of students, including exploratory play and expeditionary learning.

Compatibility can be understood through the student-led design of the Discovery Woods in Arlington, VA. When the fifth-grade students embarked on a semester long design challenge to re-imagine an outdoor space for learning – the result was the reclaiming of a natural forested area and the design/build of a multifunctional outdoor camp to promote interdisciplinary collaboration. The Discovery Woods, a forested space adjacent to the soccer fields, can serve as an outdoor project area for wildlife guest experts, a project space for art and science experiments, a reflection space for small-to-large gatherings, a place of respite, and host to other school and community events. The new immersive nature space created by students – for students, provides for what intuitively drives students to think, make, do, and be at school and beyond.

Therapeutic Lens for Learning – in Action

When talking to students immersed in the rooftop haven for urban agriculture at the Gary Comer Youth Center in South Side Chicago, Illinois, we realize the power of nature’s restorative effects through the remarkable contributions each student continues to make within their local community. In her heart-to-heart conversation with student leaders of Comer Crops, a food systems internship on the Comer Campus; Ty Bailey (they/them/theirs), Asha Simmons (she/her/hers), and Ammon Styles (he/him/his),

Urban Agriculture Director Marjorie Hess makes the case for learning in and from nature as we listen into the profound lived experiences of how and why the garden in the city has led each student to discover and apply their leadership skills for community impact. As an example of all four attributes of therapeutic environments combined with educational programming synergized with the needs of local families, neighborhood, and school, the rooftop farm provides a real world setting from which students can learn and apply a wide range of important skills.

“There’s a lot of academic information and statistics about what urban agriculture does and how it impacts community,” says 21-year-old Chicago native and Comer Crops intern Asha Simmons (she/hers), who has a background in agricultural economics and is pursuing a master’s degree in food studies at New York University. “But working in the space you know that it’s much more and it hits different. It feels more impactful.” An educational resource based on an interdisciplinary approach combined with real-world applications, the 8,000 sq. ft. urban garden functions as a real source of fresh, organic food for the center’s kitchen, four local restaurants, as well as for selling at special Farmers’ Market events. “It is very important to make an environment in which people feel included in their work,” says 21-year-old Ammon Styles (he/him/his), Comer Crops intern and civic leader. “If you see yourself as part of the food system, you can apply that mindset to the rest of your life and feel empowered to make change and advocate for yourself in other communities.”

As the physical heart of the architecture, near and far views to the rooftop farm guarantees the restorative effect of total well-being for students and educators. “I’m most at home when I’m in nature,” shares Ty Bailey (they/them/theirs), Comer Crops intern. “That’s why I think it is so important outside spaces need to be accessible to all people. When outdoor spaces are not accessible, we prevent people from feeling the joy of being in nature.”

Conclusion

Designing school settings that also include physical attributes that are ‘restorative’ for mental health can enhance wellbeing and increase learning opportunities for children and adolescents. For the first time, we set out what these four attributes of a restorative environment might look like in a school context. We invite you to download the EDpaces 2020 session (ES20WB1) on this topic to discover what it means to create holistic well-being for all students and educators as early as possible in the design process to serve every student at the highest level of their total wellbeing.

Article References

Berto, R. The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394-409.

Bianchini, R. Youth center’s vegetable roof garden provides food for children in Chicago. Inexhibit, www.inexhibit.com/case-studies/youth-centers-vegetable-roof-garden-provides-food-for-children-in-chicago; 23 July 2019.

Evans, G.; Cohen, S. Environmental Stress. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Stokols, D., Altman, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 571–610.

Kaplan, S. 1995. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 15:169–82. doi:10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2.

Kaplan, R., and S. Kaplan. 1989. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Google Scholar.

Ohly H, White MP, Wheeler BW, Bethel A, Ukoumunne OC, Nikolaou V, Garside R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2016;19(7):305-343. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2016.1196155. Epub 2016 Sep 26. PMID: 27668460.