From more engagement and less stress to improved physical and psychological well-being, research has proven the numerous short- and long-term benefits of outdoor learning. In July 2016, the Natural Connections Demonstration project, funded by Natural England, published new evidence on these benefits to students, teachers, and schools after a four-year initiative to help school children experience the benefits of the natural environment by empowering teachers to use the outdoors to support everyday learning.1

Key findings:

- 92 percent of teachers reported their students were more engaged and 85 percent saw better behavior.

- 92 percent of students said they enjoyed their lessons more, with 90 percent feeling happier and healthier.

- 79 percent of teachers reported positive impacts on their teaching practice.

- Almost 70 percent of teachers experienced improved job satisfaction and 72 percent reported improved health and wellbeing.

Research also shows students can better retain what they have learned when they can apply it to real-world scenarios. An American Institutes for Research (AIR) study on the effects of outdoor education programs for children found that among academic gains were social studies, language arts, math, and science — where science test scores increased by 26 percent. The study also confirmed that the more confident a student felt about a subject, the hungrier they were to learn more.2

The Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE) and HMC Architects (HMC) released Design Guidelines for Outdoor Learning in June 2021 as a tool to engage, encourage, and empower educators to create successful outdoor learning environments.

HMC spoke with Shaun Hawke, an educator and project director of LACOE’s Outdoor and Marine Science Field Study program, and Jema Estrella, LACOE’s director of facilities and construction, to discuss ways to address educators’ concerns and set them up for successful programming, design, construction, and implementation of an outdoor learning environment.

Setting teachers up for success

HMC: Teachers do not always know how to best utilize and teach in an outdoor learning environment. They are concerned about how the space will affect how they teach and how students will be able to learn.

Hawke: Most teachers feel confident teaching in the comfort and constant conditions of an inside classroom. However, when faced with the dynamic and numerous variables of outside conditions, they may feel the effort to adjust and rethink the teaching process outside just isn’t worth the trouble. Yet those same challenging variables bring exciting phenomena into the learning process. Nothing can enliven a lesson and excite students like an influx of genuine phenomena such as snow or leaves or insects. The joys and health benefits of being outside can also engage students in ways many teachers have never witnessed.

HMC: Many teachers believe only science, art, and physical education lessons can be taught outside. How have you seen other teachers successfully teach their subject outdoors? What kinds of teaching tools, resources, and equipment should be considered?

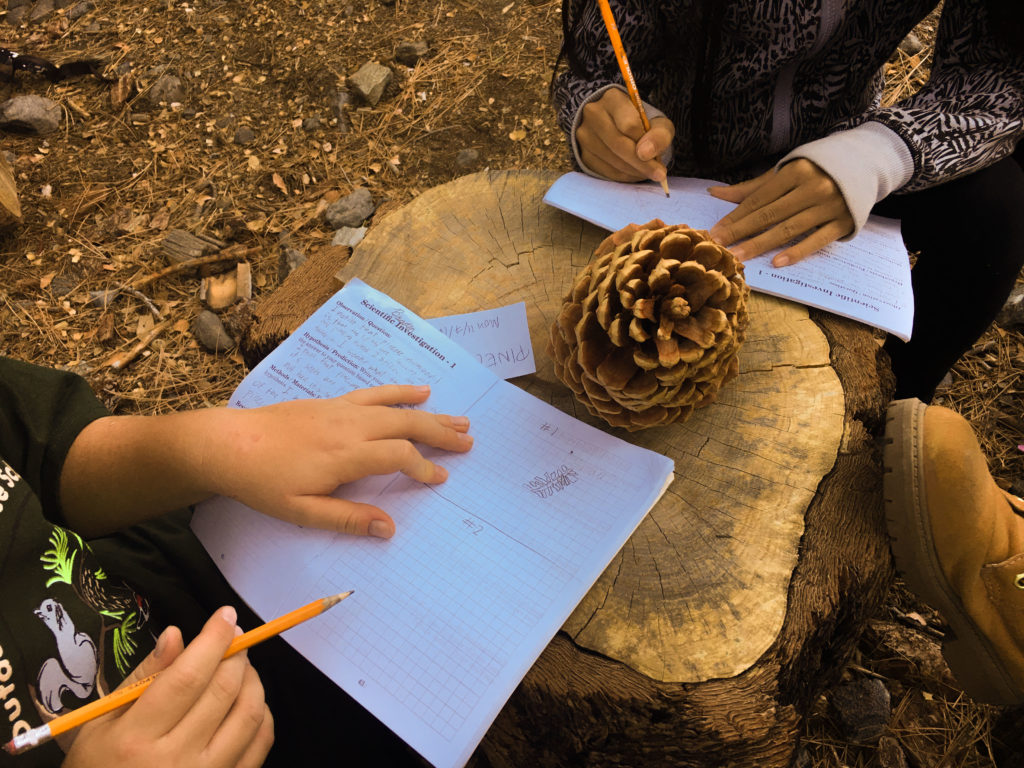

Hawke: Any subject taught inside can be taught outside, except for those lessons that require significant technology or lots of materials. If a lesson can be converted into a ‘low-tech’ version and basic necessary equipment such as writing surfaces can be found, that lesson could very likely work outside. Clipboards, a large whiteboard, and foam pads are three of the most efficient and inexpensive ways to transition almost any lesson outside.

HMC: How do you keep students’ attention during the lesson, and not have them become distracted by phenomena around them? What creative ways or strategies have you utilized to integrate phenomena into your lessons? What types have you found most engaging by students?

Hawke: Children are most engaged by things they can see or touch. Like adults, they especially like living things and unusual things, so integrating those special things helps keep kids focused. Animals, leaves, even grains of sand seen through a magnifier can get them excited. Many times, I’ve been teaching students from the L.A. basin up in the mountains when it began snowing. Kids seeing snow for the first time will interrupt absolutely EVERYTHING! But what a powerful learning experience. So, it isn’t always possible to keep them engaged in what you want to focus on. The best approach to keeping students’ attention is to teach about whatever is capturing their attention. That’s not always easy to do, but any way to connect a topic with what students are interested in can keep students engaged in meaningful learning.

HMC: What do you say to teachers who think outdoor learning is ONLY for states with nice weather? How can you take learning outside into rain, snow, and windy conditions?

Hawke: Snow and rain are such tangible and interesting phenomena for kids. If students have good gear for rain or snow, they have a great time outdoors. Teaching in those conditions can take some thought, however. Melting snow to check the water content is fun to guess and mapping where water goes on campus when it’s raining can be a great discovery process for students. While extreme weather can make outside learning a challenge, ordinary examples of snow or rain can be exciting to study. Those difficult conditions may also require some flexibility, such as having kids collect information or data and then coming back inside to record those things on paper or a device.

HMC: What’s the worst outdoor learning environment you have encountered and how did you make it work?

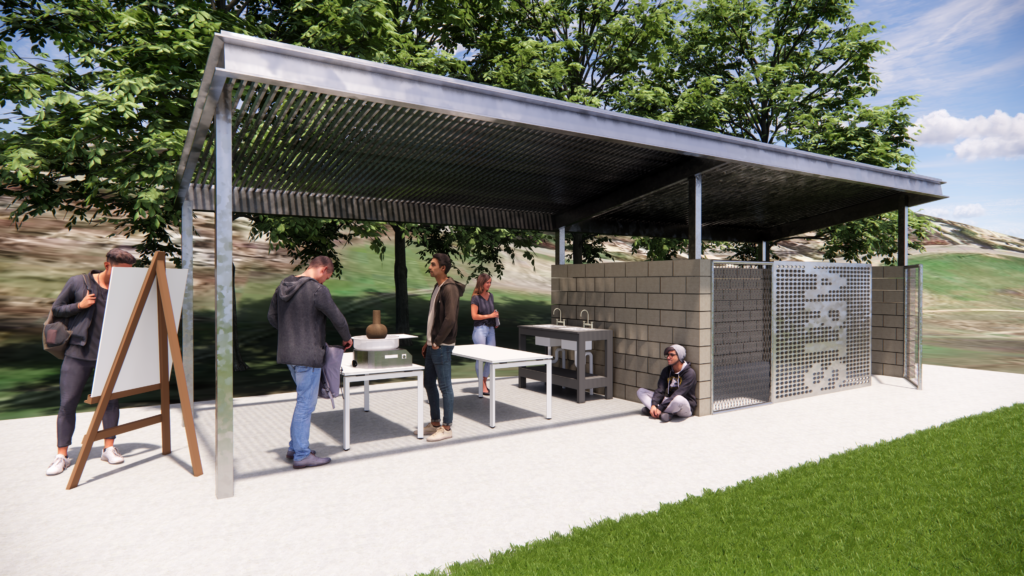

Hawke: The worst learning environments I’ve tried to teach in are usually those that are windy, either in hot or cold temperatures. If the wind can blow dust or snow into students’ eyes, it can be too much to deal with successfully. Finding an area sheltered by a wind block can suddenly make the learning environment workable. A close second worst area is one that is sunny and hot with no shade. A classic example is a blacktop on a schoolyard which acts as a heat sink. Schoolyards with large blacktops can be over five degrees hotter than the surrounding areas making a hot day that much worse. Wind blocks and shade of some kind are often the essential ingredients that can make the most challenging conditions more comfortable.

Addressing the administrators’ concerns

HMC: What kinds of professional development is needed for teachers to successfully embrace and teach outdoors? How does a teacher plan and balance play and curriculum outdoors? How can I ensure my staff will utilize and embrace outdoor learning?

Demonstrating an engaging lesson for teachers in an outdoor space can give them the confidence and ideas to implement their lessons.

Hawke: Teaching outdoors is always place-based, meaning there are a variety of assets and conditions unique to each outdoor space. Because of all the variables of each space, professional development should start with taking educators outside on the school campus where they would be teaching. Demonstrating an engaging lesson for teachers in an outdoor space can give them the confidence and ideas to implement their lessons. Once students get into a routine and have parameters clearly outlined, they will focus on lessons outside just as they do inside. Finding an educator with experience teaching effectively outside to lead that professional development may be the biggest challenge for a school or district. A good place to find experienced outdoor educators is at a county office of education to see if they have any outdoor education programs.

HMC: How do you decide who can use the space? How do you encourage its use or prevent someone from dominating its use? How is scheduling / reserving of these outdoor learning spaces best handled?

Estrella: First, the principal needs to identify who are those key teachers who need to use the outdoor space and who will be committed to using it. Then consider what other teachers or groups should be encouraged to use the space and how to make it equitable for all the teachers and competing interests. Over the years principals have developed different strategies for scheduling and reserving the outdoor spaces:

1. Have a rotating schedule. For example, on Tuesday/Thursday one particular group of teachers schedules the use of the space for either the mornings or afternoons.

2. Develop blocks of time that different programs can reserve the space.

3. Keep a calendar where teachers and groups can reserve the outdoor space for their lessons.

The scheduling of the space is as unique as outdoor learning and identifying a strategy for scheduling that works for everyone must be developed. This will encourage everyone to utilize the space.

HMC: How are students kept safe while using an outdoor classroom when there is an emergency on campus?

Estrella: When we are indoors, depending on the emergency, our action may be to go outdoors. If there is an emergency outdoors, we need to have the ability to pivot and relocate quickly. Part of outdoor learning is having the flexibility of the environment, hence the element of flexibility and quickly being able to relocate to another place is important and it depends on the type of emergency. If it’s an earthquake, which is common in California, the students and teachers are much safer outdoors than indoors. So, when your campus is determining where to locate your outdoor learning space, consider what is around it. Are there any hazards, like a power pole that you want to avoid?

Creating an outdoor learning space is simpler than most think and educators will see the return on this creative investment quickly. After spending the last year mostly indoors, isolated, and in front of a screen, it’s more evident now than ever that young students crave connectedness with the natural world.

About HMC: Founded in 1940 with the purpose of anticipating community needs, HMC Architects aims to create designs that have a positive impact, now and into the future. We focus primarily on opportunities to have the most direct contribution to communities — through healthcare, education, and civic spaces. HMC has 304 employees and six offices throughout the state of California. Learn more.

About LACOE: The Los Angeles County Office of Education, based in Downey, is the nation’s largest regional education agency, providing a range of services and programs to support the region’s 80 school districts and some two million preschool and school-age children. Learn more.

References

1Natural England (2016) article, England’s Largest Outdoor Learning Project Reveals Children More Motivated to Learn When Outside from GOV.UK, England’s largest outdoor learning project reveals children more motivated to learn when outside – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

2Plant a Seed and See What Grows Foundation, cites findings from an American Institutes for Research (AIR) study in their post The Key Benefits of Outdoor Learning / Education for Children and Teens, Benefits of Outdoor Education for Middle School Age and Teens (seewhatgrows.org)