Recent tragic events have brought renewed attention to how school sites are selected and buildings are constructed. The challenge in both issues is how to balance creating a school that is safe and secure yet is welcoming and promotes a positive learning environment. This need has brought about a renewed interest in CPTED – Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.

The first step in implementing CPTED principles in either new construction or a redesign project is stakeholder participation.

What is CPTED?

CPTED was first developed in the early 1970s as the result of studies that showed proper site selection and building design could not only reduce the incidence of crime, but also the fear of crime by those using the facility. There are numerous publicly available sources of information on CPTED, and while some may vary slightly in the use of terminology, there are some generally accepted principles:

- Natural Surveillance: this refers to clear lines of sight in outdoor spaces between the building and road. Visibility improves the chances for detection of potential threats. Natural surveillance also extends to proper lighting. Care should be taken that trees and shrubbery do not impede the ability for people to observe or electronic surveillance equipment (particularly cameras) to focus on an area.

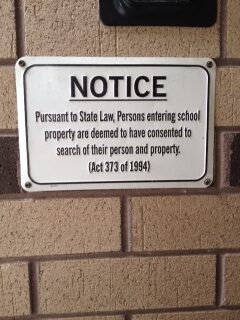

- Natural Access Control (Access Management): these type of barriers can be real or symbolic. Signs are a passive control method, while fences, gates and doors serve as physical methods. Landscaping, such as trees and shrubbery can serve as a hybrid method which, while easily circumvented, serve to channel people into desired pathways.

- Territoriality (Territorial Reinforcement): establishes ownership through the use of signage, fencing, landscaping and pavement treatments. Clear borders should be established at the outer edge of the property and the message should be reinforced the closer one gets to the building. Territoriality should be welcoming, such as using school colors and mascots, but also direct, as in signs directing all visitors to report to the main office.

- Maintenance: The “Broken Windows” theory from the 1980s posits that leaving broken windows, graffiti and trash unaddressed leads to the impression that no one is concerned about the facility and that misbehavior and crime are acceptable. Removing graffiti and making repairs to windows, fixtures and lighting shows pride of ownership and reinforces Territoriality.

Implementing CPTED

The first step in implementing CPTED principles in either new construction or a redesign project is stakeholder participation. Schools are part – and often the center – of a community. Planners and designers need to consider that in addition to education, schools serve as cultural, sporting and recreation centers. Representatives from these groups can provide insight into how the campus is used outside of the educational setting. Involving stakeholders also bolsters Territorial Reinforcement.

It can be helpful to engage a trained CPTED site assessor to make recommendations on how safety can be improved. Assessors typically start by looking at the neighborhood or community where the school is located, including the proximity of first responders. The assessor will review the school’s policies and procedures to see if they are appropriate to the school’s location.

The site assessment usually will begin at the farthest point on the school property and progress inward. The assessor will look at property access points, how they can be controlled (fences, gates) and how traffic flows both in and out of the campus. Is there property signage and road markings? Are there separate access points for buses? Are there line-of-sight impediments that would hinder the ability of staff or cameras to view the perimeter of the property? Some other considerations include:

- If fencing is used, is it in good repair (no bent places or holes)? Are gates secured by locks? Is there a policy or procedure stating when gates should be locked?

- Are dangerous or vulnerable areas such as utility stations, culverts or retention ponds clearly marked and fenced?

- Are pedestrian spaces clearly defined, separated and protected from vehicle pathways?

- Are parking areas clearly designated and properly lit?

The next step in the assessment process would be inspecting the building’s exterior. Visitors should be greeted by signage directing them to the main office. Plants and shrubbery should be trimmed and separated so they do not obstruct cameras, and cannot be used as a hiding place or as a way to access rooftops. Other factors to consider when inspecting a building’s exterior include:

- Are the grounds and building free from graffiti, trash and debris?

- Are exterior doors and windows numbered so they can be seen by First Responders?

- Are all exterior doors secured and hardware removed, except from those used as designated points of entry?

- Is access to utility areas secured?

- Are there exterior speakers and/or strobe lights to provide emergency notification to students and staff outside the building?

- Are playgrounds secured and able to be properly monitored by staff and cameras?

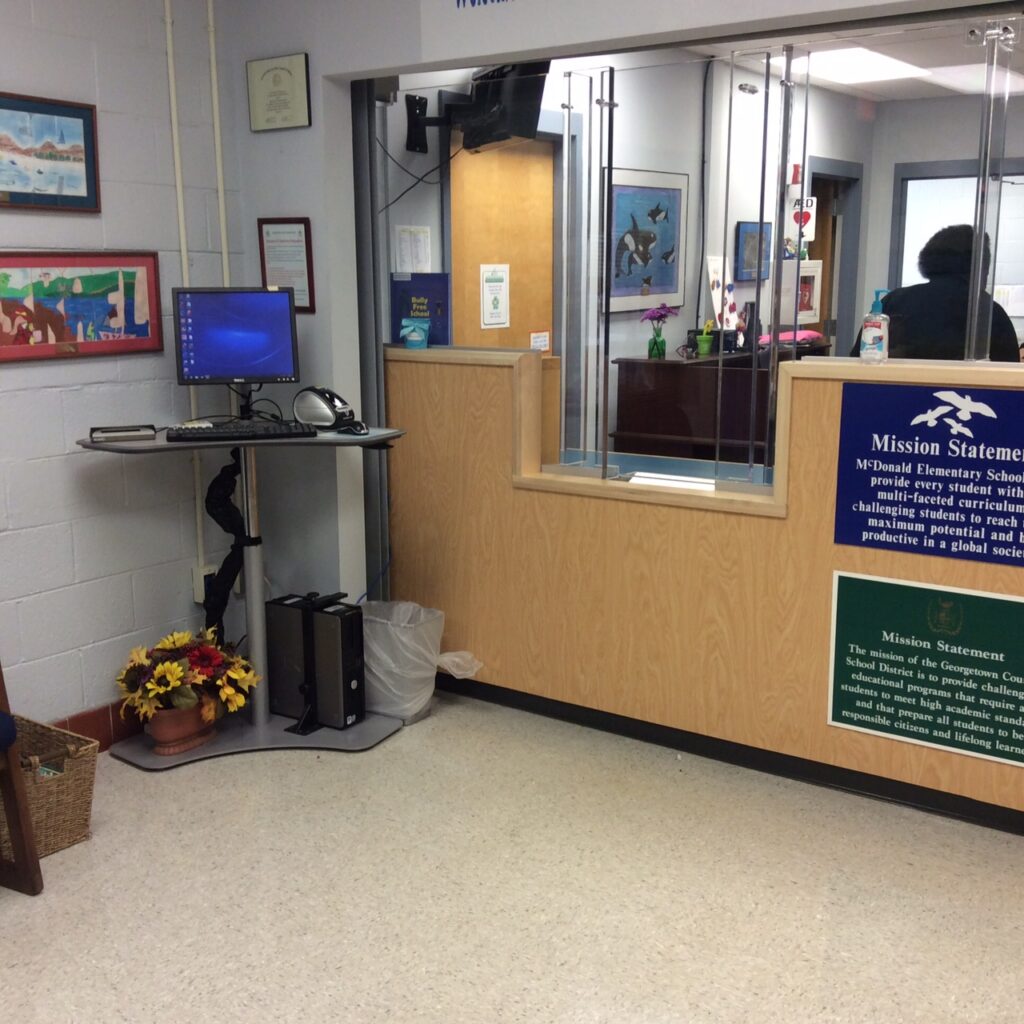

Moving to the interior of the school, the first consideration would be access control. Is there a single point of entry to the main office? How is access granted and monitored from the entry point to the office? Many new schools are being built with, and older schools retrofitted with, secured vestibules. Sometimes referred to as “man-traps,” these passageways can be monitored by line-of-sight observation, cameras, or both. Other items to be checked include:

- Does signage identify the location of emergency equipment, such as AED’s and fire extinguishers?

- Are maps and directories posted in prominent locations?

- Are hazardous storage areas and mechanical rooms locked?

- Do emergency exits have alarms? Do they have crash bars? Are they self-locking?

- Are there blind spots not covered by cameras and difficult to see by staff?

These are just a few of the issues that can be addressed through CPTED. It is important to remember that if outside assessors are used and their recommendations aren’t followed for certain corrections or improvements, civil liability could result for the school’s governing body should an incident occur.

CPTED continues to evolve from its original premise that included the “4 D’s” of deter, detect, delay and deny. Second generation CPTED expanded to include social cohesion, community connectivity, community culture and threshold capacity (the community’s ability to balance land use and urban features). Now there is a burgeoning third generation of CPTED that adds sustainability and green technologies into the mix. School planners and designers should be encouraged to learn more about how incorporating CPTED principles can lead to safer and more functional school facilities.