High-quality childcare and early childhood education provided at early learning centers (ELCs) profoundly impact the immediate and long-term socioeconomic well-being of children, their families, and their communities.

The average American family spends more than a quarter of their household income on childcare. These hefty fees trigger a ripple effect on businesses, driving parents out of the workforce, but it doesn’t end there. Parents driven out of the workforce spend less, earn and invest less when they return, effect area-wide labor shortages and a reduction in tax revenue, all of which have a negative compounding impact on families, the communities in which they live, and the larger economy. Since ELCs also serve as incubators for a skilled, resilient, and socially adept workforce, they can shape a region’s economic landscape for future generations. Plain and simple — childcare and early childhood education are the backbone of our economy.

In South Carolina, many young children face challenges that can be barriers to success in school and life. Early childhood education through school-readiness programs help remove these barriers for children.

Investing in high-quality early childhood learning centers is an investment in human capital that community leaders and corporate partners (as drivers of the workforce economy) should consider making together for their mutual benefit. Project Greenhouse in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, aims to provide a future-ready, 45,000-square-foot center for families with young children and demonstrate how strategic partnerships can elevate an early childhood education program to benefit the greater community.

Project Greenhouse

Middle Tyger Community Center (MTCC) in Lyman, South Carolina, operates an award-winning early education program within a childcare desert. Because tuition is offered on a sliding scale based on income, the program is competitive, with enrollment limited to 60 children.

Recognizing the community’s need for more high-quality childcare, MTCC leaders reached out to a long-time philanthropic supporter: a large corporation with manufacturing plants within the community whose employees would greatly benefit from such a facility. The institution agreed to fund a significant portion of the project, saving taxpayers money while proactively combating potential future labor shortages. And yet, this corporation is going even further by not reserving any spaces for their employees so that everyone in the community will have equal access.

A child care desert is any census tract with more than 50 children under age five with either no child care providers or so few options that there are more than three times as many children as licensed child care slots.

The joint venture team partnered with various entities, including the South Carolina Department of Social Services, and received a land donation from the local school district to transform the wooded property into a two-story Middle Tyger Child Development Center with offices on the second floor for the school district.

“We chose the name Project Greenhouse because the center will grow strong kids before they are transplanted into the school system, similar to how a greenhouse nurtures seedlings into hardy adult plants,” according to Haley Grau, Executive Director for Middle Tyger Community Center, which will operate the new facility. “This vision was conceived by the Purchasing, Facilities, and Safety Director of the corporation funding the project.”

The project’s collaborative approach relieved each organization’s burden while ensuring the program provides local children with a competitive early childhood education statistically proven to reduce reliance on government welfare programs, incarceration, and violent crime rates.

Project Greenhouse will provide care for 260 children, with the potential for an additional program expansion for over 300 students. A staff of more than 40 educators will keep the teacher-child ratio low to ensure engagement with the quality curriculum and compliance with state regulations.

“We wanted to design a successful ELC program, not a daycare,” Grau said. “This requires extensive collaboration, knowledge of early childhood education best practices, and trust.”

Design that inspires learning

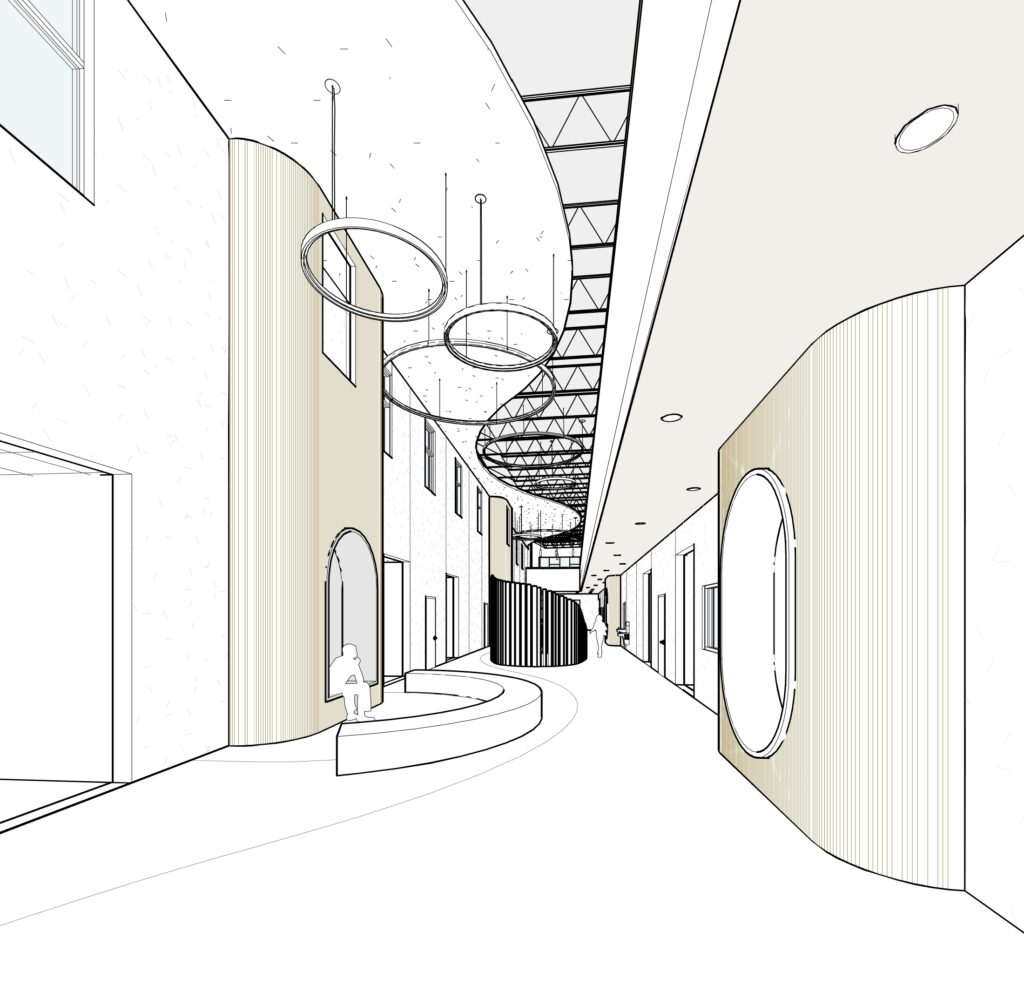

Spartanburg County First Steps provided a program framework and offered the team’s design partner, McMillan Pazdan Smith Architecture, valuable feedback to develop a facility that would meet each stakeholder’s vision for the center. The design team, led by Claudia McAninch, AIA, designed the new development center to prioritize safety, pedagogy, and community.

The one-way student drop-off and pick-up lane eliminates multi-directional traffic, and most parking is adjacent to the building to decrease pedestrian traffic along the drive aisle. Additionally, angled parking spots improve safety by making it easier for cars to move in and out. Landscaping around the facility will provide privacy and separation from nearby traffic.

The main lobby is located in the corner of the L-shaped building for ease of access and to reinforce communication between teachers and parents who walk their children inside the center. Seventeen classrooms, all located on the 33,000-square-foot first floor, are divided into two halls. The first of these wings is smaller and dedicated to infants and one-year-olds. Classrooms for children ages two through four are located in the second wing — an intentional design choice providing noise control between infants/one-year-olds and toddlers.

To promote outdoor learning, McAninch and her team designed the outdoor play areas to be an extension of the classrooms and have provided areas for art, exploration, and gross motor skills development. These recreational spaces were designed to be inclusive, even beyond the standards mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act and locally adopted accessibility code. For instance, there are no steps or ramps from the parking spaces to the main entrance, throughout the entire first floor, or from the classrooms to the outdoor play areas.

Another stakeholder priority was employee engagement and retention. The thoughtful design incorporates private gathering spaces for faculty and staff, including a dedicated courtyard. The intentionality of the facility’s aesthetic is perhaps most evident in how the team integrated ties to the local industry, including precast concrete wall panels, a nod to the manufacturing roots of the corporation funding Project Greenhouse.

Additional design highlights include:

- Abundant daylighting

- Direct access to the exterior from each classroom

- Dedicated floor/play area in each classroom

- Teacher training/behavioral observation rooms adjacent to classrooms

- Toilets connected to classrooms

- Cubbie/storage areas within classrooms

- Dedicated diaper changing areas and hand washing stations

- Dedicated food/bottle prep areas

- Flexible teaching spaces + additional rooms for parent and family services

- Parent/guardian access that promotes child development while balancing safety/security

- Centralized laundry and warming kitchen

Supporting children and families

A successful ELC model empowers parents to actively participate in their child’s education. After all, classroom learning is an extension of the learning taking place at home. To that end, Project Greenhouse incorporates multipurpose and meeting rooms into its design. Located on the first and second floors, these can be used for parent classes and family development courses.

Middle Tyger Child Development Center’s design embodies the program’s mission to improve early education access for all families. The classroom-adjacent behavioral observation rooms will facilitate teacher training, enabling the center to continually enhance its program and develop the next generation of local educators.

Replicating the Project Greenhouse program model

Corporations looking to build an ELC in their community may have the funding to construct a facility but not necessarily the expertise to design and implement an outstanding program. To begin, they should engage non-profit organizations that can source trained educators and manage operations. Collaborating with design and construction partners with a robust portfolio of early childhood education projects also plays a pivotal role in creating successful and sustainable early learning centers.

By investing in a solid educational foundation, communities and their corporate partners can position themselves to excel in highly competitive industries. Research consistently underscores that children exposed to high-quality early learning experiences exhibit enhanced cognitive abilities, improved academic performance, and greater social and emotional well-being. As they mature into contributing members of society, they bring skills and competencies that can contribute to individual success and enrich their community — a win-win for local businesses and the communities they call home.