Environments for learning should be deliberately designed for how learning happens, in all its social complexity. This statement is the premise of the article “Making Space for Learning” (Gonzalez, P.G., Noh, D. & Wilson, D., 2022), members of the Project Zero team (PZ) who conducted a literature review looking to connect teaching practices, learning, and design. The authors questioned, “To what degree are the spaces in which we learn designed with learning in mind?” This team examined what is known about the qualities of spaces supporting learning, offering guiding principles for designers of learning spaces to consider, and highlighting teachers’ pedagogical choices within spaces as the most important factor impacting student learning outcomes.

The “Making Space for Learning” article was examined as part of a course within Level 1/Foundations by students in the EDmarket Certified Learning Place Specialist (ECLPS) program. A conference workshop was also generated to determine if we can see a ‘proof in the concept’. Examination had multiple parts: (a) use the designs developed for EDspaces 2023 conference areas and apply two analytic techniques — photographic traces and annotations, and (b) at the same conference generate, using supplied found objects, a learning place and annotate with icons from the research how these solutions fit the specific needs. Next, these two items were compared to determine if cues from design can be ‘seen’ relative to the needs defined for educators. The process and findings are shared.

Thinking About Design’s Impact on Learning Processes and Outcomes — the Background

First, some background. These PZ authors’ whitepaper offers some guiding principles for the design community based on a pattern analysis. The authors argue that, “Environments for learning should be deliberately designed for how learning happens, in all its social complexity…and pedagogical experiences must unfold within these spaces (pp. 2 & 12). They further add that, “Designing spaces with affordances (i.e., furniture, technology, equipment, etc.) for learning must consider learning as both a process and an outcome. That is, spaces for learning must not only support what is learned but how learning happens” (p. 2). The Venn diagram (the authors’ Figure 1 with permission) explains that interconnected thought process.

Second, the Linking Learning Practices and Spaces segment of their paper focuses on learning practices, “… [which] are processes learners engage in that build attitudes, knowledge, and skills. Research has long investigated a range of socio-cognitive learning processes of individuals, dyads, and groups… Looking across this work, processes can be loosely grouped into types of learning practices, including but not limited to learning practices of noticing, wondering, and helping” (p. 3). These three practices — noticing, wondering, and helping — become the ‘Learning Practices’ area of the Insight Guiding Principles (Figure 2). A short description of these categories of practices include:

- “Noticing is a core learning practice with processes that focus learners’ attention through slowing down for close observation, looking, listening, thinking, and feeling (Tishman, 2018).

- Practices of noticing often lead learners to practices of wondering, in which they are curiously asking questions, creatively exploring, and actively experimenting (Clapp, 2017; Ritchhart et al., 2011)…

- As learners confront uncertainty and doubt, they often turn to others for advice, ideas, and support lead to practices of helping include learners asking for and offering input, feedback, and guidance (Aleven et al., 2003; Calarco, 2011; Webb et al., 2006)” (p.3).

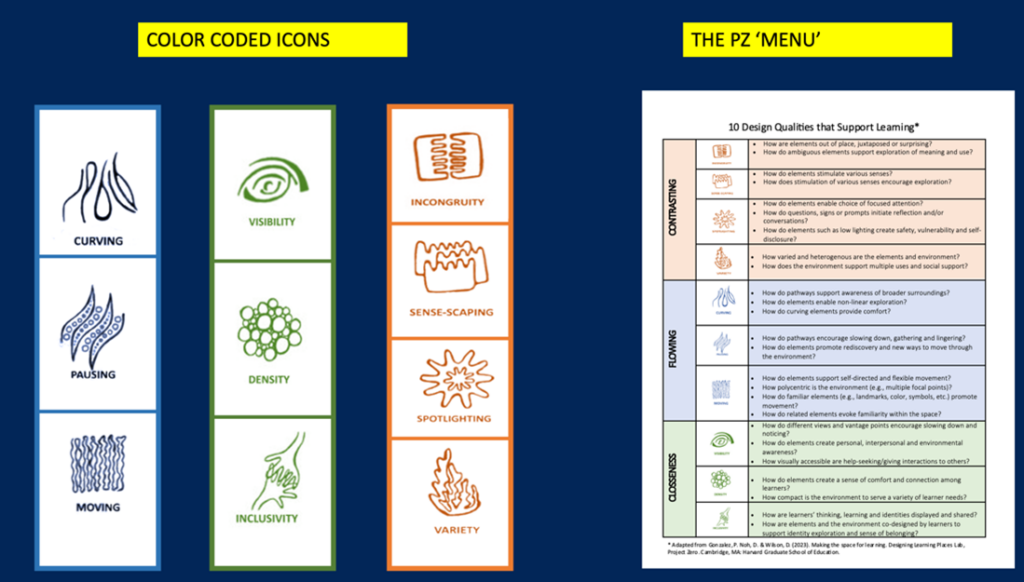

After reading over 100 research articles, the PZ authors recognized a need to generate a further component of the guideline — Qualities of Spaces. “Through iterative cycles of sensemaking, the authors distilled the following research-based qualities of space, objects, and materials that support learning practices of noticing, wondering, and helping” (p. 3). That distillation resulting in three categories of Qualities of Spaces as: Contrasting, Flowing, and Closeness with each having multiple subcategories (Figure 2).

- Contrasting is described as: “When spaces, objects, and materials conflict with expected perceptual patterns, they create affordances for noticing, curiosity, and exploration” p.3). Under this quality lies information about sub-factors including Incongruity, Sense-scaping, Spotlighting, and Varying.

- Flowing is about the ability to move and having agency over the types of movement needed throughout a learning time. This category is further explained by the addition of Curving, Pausing, and Moving. The third quality category is Closeness.

- “…closeness and connectedness are also important qualities for creating social conditions that promote help-seeking, observation, and curiosity. Spaces that evoke feelings of closeness and connectedness foster relationships and a sense of inclusion within one’s environment” (pp. 8-9).

Closeness is further explained with the words Visibility, Compactness, and Inclusivity as sub-section. Each sub-section throughout had its own descriptor in an effort to link learning practices and the qualities of space. The Insights Guiding Principles Matrix (refer back to Figure 2) was established to literally help guide designers when planning for learning experiences. As an insights guide, it allows one to look at how qualities of space might influence learning practices, or vice versa. Interesting work. The questions for Scott-Webber of this white paper were, “If architecture provides ‘cues’ (Harrouk, 2020) for our behaviors, how might we begin to ‘see’ these qualities in space? Are there attributes from this Insights Guide which might be taught? If so, how might one put these insights guidelines into practice? Could we begin to ‘prove this concept’? A project assignment started the process of trying to prove the concepts and make this kind of thinking actionable.

The Method

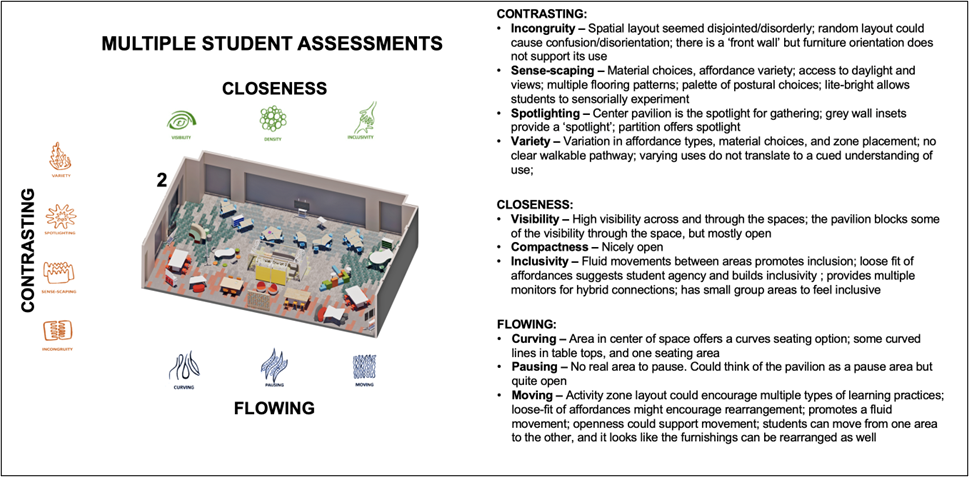

Several scenarios examined this white paper’s findings, and it all started with a student assignment from the ECLPS Level #1/Foundations program. The project challenged 20 students in the ECLPS program review two designs each [n=24] [studies as ‘photographic traces’ (Zeisel, 1998)] submitted to EDspaces for a spot as a conference learning setting (Figure 3) as a convenience sample. [Please note. The designs submitted had different criteria, but this assignment just used them as available designs generated to at the very least allow for active learning engagements]. Then they were asked to use the Insight Guideline Matrix items and analyze the ‘fit’ using an annotation analysis technique (Wilkins, 2023) (see Figure 4).

For our purposes, “An annotation might look like highlighting information or vocabulary in a text, marking a text with symbols to represent different ideas, creating notes in the margins of a text to keep track of thoughts and questions, or writing summaries at the end of a chapter or section for easy review.” An example of one student’s work is shown in Figure 4. The annotations used drawing arrows and/or words pointing to the places on the image where the student felt there was a ‘fit’ between the description of the word and the cues from the image shown. [Note: the Thornburg’s (2014) spatial archetypes (e.g., cave, campfire, etc.) were a part of the original design submittal and not a part of this exercise].

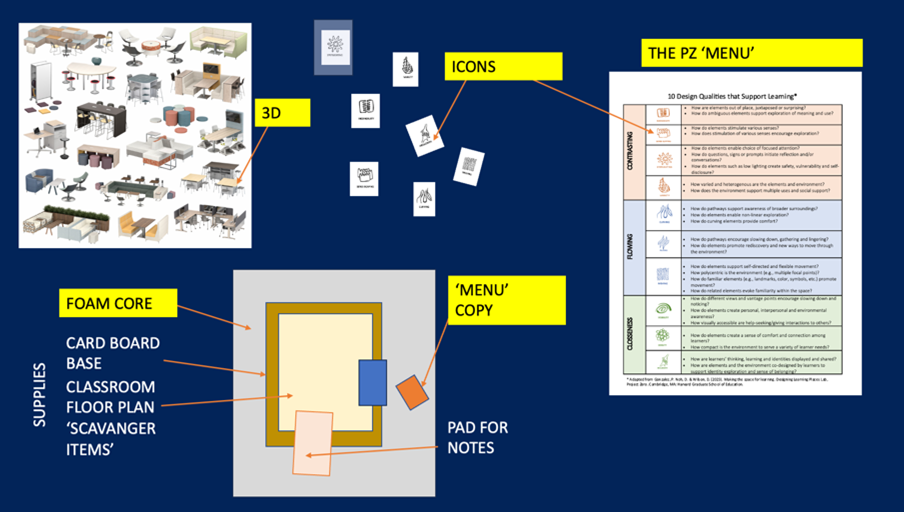

The next step in the process was to present a workshop at EDspaces conference in 2023 (Scott-Webber et al, 2023). One of the PZ white paper’s authors joined with three others to present with the purpose of proving the concept. Each of the 8 tabletops were given a scaled floor plan, the PZ ‘Menu’ of insights, 3D affordance pieces as provided by The MiEN Company, lots of various ‘found objects’, and cut outs of all of the different items in a color coded ‘menu.’ This menu was adjusted slightly to have attendees focus on quality items (Figures 5 & 6).

Workshop attendees were placed in small groups approximately 8-10 per, used the research Insight Matrix Guide to discover if/when using found-items to represent affordances (e.g., furniture, technology, equipment, etc.) in a scaled floor plan, could they could demonstrate a link between their table top design solutions (Figure 7) and these findings. Then, attendees started to work on these questions. About 80 people were in attendance. Once the work was done, sharing of the ‘findings’ were presented and audio recorded. The final step was to look for patterns from the tabletop workshop. Recordings of attendees’ presentations were reviewed for this purpose.

A ‘Proof of Concept’ / Findings

Of the six designs analyzed by students, only two seemed to connect on all points offered in the Insights Guide model (Figures 8 & 9). It is argued here, that although the ‘students’ in the ECLPS program are all working professionals some concepts are perhaps not easily understood — or cueing for these needs a better explanation. Incongruity is one example of this perceived need for more clarity of what it might look like in a learning space.

The pattern analysis from the students’ assignment yielded an affirmation that students could discern the architectural cues in designed space as offered by the Insights Guiding Principles as shared in the PZ white paper. Some items from the guide perhaps need further ‘guidance’/clarification/examples to ensure what is meant can be seen.

The pattern analysis from the workshop proved to be more challenging from the conference facilitators perspective. Lessons we learned include: (1) take photos of the final table top solutions that are clear and unencumbered; (2) make sure the small group members place the icons representing the principles on the solution where that item is emphasized so we may interpret these more clearly at a later date; and (3) record insights attendees provided. All that to say, we were not able to generate a pattern analysis protocol with the attendee solutions.

Reflection insights from attendees included:

- “I think this was really helpful [connecting the activity to the research article], and I really wish we were being a little more intentional with our own designs and educational ideas from the get-go. I would like my team members to be thinking this way from the beginning.”

- “If the glass walls aren’t broken, and the architects, and the educators, and the people who design the furnishings all don’t work together as one, everything freezes, everything stops, and innovation dies.”

- “Exceptional children are a group not often considered when we look at innovation and renovating spaces. I like that it was brought up in this session.”

- “I would think we should do this activity with the people we do the education specification process with right from the very beginning. If so, we would be in a place where we’d get the most thought-provoking different realities.”

The Conclusion

The Insights Guiding Principles as offered by the Project Zero White Paper provides an interesting perspective, perhaps ‘lens’ for generating design solutions to ‘fit’ learning practices. The matrix provides valuable clues for how one might generate architectural ‘cues’ in space itself. Their premise is that these categories help link learning practices with spatial attributes. As one such tool it is helpful. And as seen by these learners — somewhat attainable when viewing space and its attributes. Some other takeaways could be a realization for the:

- Need for more “design principles” as direct approaches, rather than focusing too quickly on planning;

- Power of using easy to use manipulatives to mediate thinking/designing (particularly with stakeholders who aren’t architects); and

- Encouragement in using an actual design approach for learning processes that engages those very learning processes (e.g., wondering, noticing, helping).

It reminds us that as conference goers, or learners in a program of study, it is important to understand these are constant opportunities to see how participants can not only participate but also learn and actually take something away. A for sure next step is to have these questions as a final component:

- As an architect/designer/facility planner, I would “____”

- As an educator/education decision-maker I would “____”

- As a learner I would “____”.

Thanks to the following collaborators for this article from ECLPS Cohort #1:

- Victoria Brooks-Morian, Kay-Twelve

- Dave Broz, AIA, Visiting Professor, Columbia College

- Michael Bruder, Chula Vista Unified School District

- Caroline Cooney, Frank Cooney

- Ashley Compos, Chula Vista Unified School District

- Christian Frank, The MEiN Company

- Arden Herrington, Educational Environments (Frank Cooney)

- Emily Islip, Smith Systems

- Jim Kemling, Educational Environments (Frank Cooney)

- Jolene Levine, Jolene Levine, LLC

- Dustin McDermott, Marco Group, Inc.

- Nicole McGregor, Smith Systems

- Molly Miner, Gibraltar Design

- David Reid, AIA, Multistudio

- Mary Sauvageau, Red Thread

- Marisa Sergnese, Steelcase Learning

- Courtney Sevigny, VS America, Inc.

- Andrea Stingone, Hillsborourgh County School District

References

- Aleven, V., Stahl, E., Schworm, S., Fischer, F., & Wallace, R. (2003). Help seeking and help design in interactive learning environments. Review of Educational Research, 73(3): 277–320. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543073003277

- Barrett, P., Treves, A., Shmis, T., Diego, A., & Ustinova, M. (2019). Baseline conditions for learning. In The Impact of School Infrastructure on Learning: A Synthesis of the Evidence (pp. 21–29). World Bank Group. https://documents1.worldbank.org/cur ated/en/853821543501252792/pdf/132 579-PUB-Impact-of-School.pdf

- Clapp, E. P. (2017). Participatory creativity: Introducing access and equity to the creative classroom. Routledge.

- Calarco, J. M. (2011). “I Need Help!” Social class and children’s help-seeking in elementary school. American Sociological Review, 76(6); 862–882.

- Garza-Gonzalez, P., Noh, D. & Wilson, D. (2022). Making the space for learning. PZ. Project Zero. Harvard University. https://pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Making%20the%20Space%20for%20Learning.pdf

- Harrouk, C. (2020). Psychology of space: How interiors impact our behavior? ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/936027/psychology-of-space-how-interiors-impact-our-behavior.

- Imms, W., & Byers, T. (2017). Impact of classroom design on teacher pedagogy and student engagement and performance in mathematics. Learning Environments Research, 20: 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-016-92 10-0.

- Ritchhart, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011). Making thinking visible: How to promote engagement, understanding, and independence for all learners. Jossey-Bass.

- Scott-Webber, L., Wilson, D. G., Levin, J., Forcucci, K. & Broz, D. (2023). Research to proof of concept from findings, EDspaces Conference, Charlotte, NC.

- Thornburg, D. (2014). From the campfire to the holodeck. Creating engaging and powerful 21stcentury learning environments. New York. Jossey-Bass / A Wiley Brand.

- Tishman, S. (2018). Slow looking: The art and practice of learning through observation. Routledge.

- Webb, N. M., & Palincsar, A. S. (1996). Group processes in the classroom. In D. Berliner & R. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (3rd ed., pp. 841–873). Macmillan.

- Wilkens, R. (2023). Statistical methods for annotation analysis. Computational Linguistics; 49(3): 763–765. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_r_00483.

- Young, F., Cleveland, B., & Imms, W. (2019). The affordances of innovative learning environments for deep learning: Educators’ and architects’ perceptions. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00 354-y .

- Zeisel, J. (1984). Inquiry by design: Tools for Environment-Behavior Research. Cambridge; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.