As libraries renovate to expand their mission and host an eclectic mix of activities, library professionals, students, and teachers are busy reinventing the ways libraries accelerate the learning experience. Influences driving today’s creative disruption include generational differences in how students consume media and digital technology to support a range of individual learning styles, and the growing need for multipurpose, social engagement spaces.

Integrating these new uses presents a formidable challenge. How can we balance the need for louder, more interactive uses with the desire to preserve, and even enhance, the library’s quieter, more traditional study spaces? While there is no singular solution for this dilemma, a range of proven design strategies can achieve the desired acoustic balance for all activity types within a school library building.

Planning and Program Choices

With any library renovation, early discussions and decisions include how the current space can adapt its new mix of student use without departing from its traditional look and feel. Acoustic planning is an opportunistic, practical aspect of this planning and programming initiative at the start of each project.

An ideal place to begin is an assessment of what is possible, including a thorough examination of the inherent opportunities offered by the existing library’s structure. We recommend using collaborative planning and program exploration with the school librarians, administrators, and other stakeholders working in partnership with the project design team. These discussions will lead to developing a clear view of the design vision and a framework for shared priorities around sound separation. Start with the big questions:

- What are the things we want to accomplish in this library?

- What uses do we know in advance are going to be noisy and have a higher level of activity?

- Is there an opportunity to integrate teaching, meeting, or multipurpose spaces?

- What do we want to preserve and enhance about the current library’s student experience?

Separating Noisy and Quiet Spaces — Acoustic Neighborhoods

The best strategy for separating spaces by sound level is to think about distributing activities into acoustic neighborhoods. The most active spaces will be located within the appropriate neighborhood and be separated by insulated walls, doors, or even book stacks serving as sound barriers. Quieter zones, where students read or research, will be in neighborhoods that benefit from designed isolation from active group activity spaces.

A central principle of this strategy is to cluster the louder social spaces in close proximity to the library’s central traffic area — a major corridor, a central spine, a lobby, or a central atrium, often found on the ground floor. These spaces serve as the beating heart of the library, a place for exhibits, discovery, and impromptu encounters. Students using the spaces within this lively commons neighborhood will feed off the excitement, energy, and visibility.

Deerfield Academy’s Boyden Library places louder, activity-hub spaces on the lowest floors. As students move up via a central stairway, they encounter more subdued neighborhoods, with the top level dedicated to studying and reading.

Creating Sound Barriers

Once the building layout is developed and neighborhoods designated, we look at the best practical solutions to contain sound in the active, noisy spaces using doors, glass walls, or other barriers. The renovated Boyden Library hosts a diverse mix of group and hands-on learning and light prototyping, an innovation area for computer science and digital studies, two new multipurpose classrooms, and a variety of different-sized study rooms providing room for group work and social experiences.

To manage access to these rooms, we worked with the school’s librarians to create a signage and scheduling system. Breakout and team study groups can reserve a time slot via an online reservation app, or a more traditional signup system can include a whiteboard at the door.

In many libraries we visit, the removal of book stacks creates a visual void, a surplus of undefined and uninviting open areas. These available spaces, when combined with the repurposing and redistribution of book stacks, offer an opportunity to delineate quiet spaces from more active ones. A greater density of book stacks, positioned correctly, serves as an acoustic shield and a visual indicator that you are now in a quiet zone.

The multilevel Snell Library at Northeastern University features creative ways to break up undefined spaces. Like Deerfield’s Library, the level of activity tapers as you move up through its four levels. Snell’s redesign features floating “pods” on the library’s second level that break up the space and delineate an inviting acoustic neighborhood.

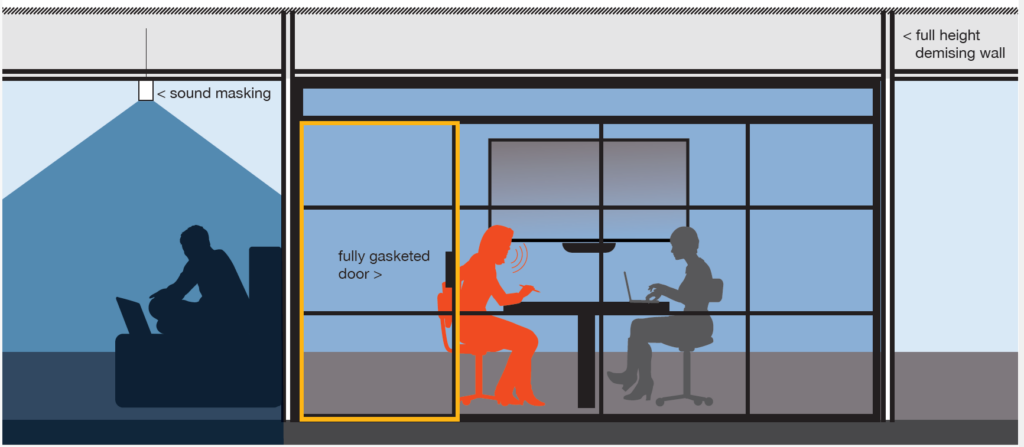

The pods — perfect for group study — are well isolated with a gasketed door and an enclosed “lid” above the ceiling. The pods are positioned to shield “quiet zones” in the open plan from the more active central circulation and stairway.

Mitigating Sound: Absorption Materials and Sound Masking Breakthroughs

Busy libraries generate a mix of sounds, often distracting those trying to read or study. The source might be as basic as people walking through a corridor, using a printer, or sneezing. A crucial factor in mitigating these inevitable sounds is controlling how far they travel. We use the term ‘radius of distraction’ to define this distance.

Plaster ceilings that reflect sound, including those in the library’s busy commons area, extend the radius of distraction further because sound bounces off them and penetrates deeper into the library. Fortunately, advancements in sound-absorbing ceilings and other materials provide designers with practical, cost-efficient options for shortening the distraction radius. Today, these beautiful materials will mimic the look and feel of historic surfaces, like plaster in an early 20th-century library or concrete if we are renovating a mid-century modern brutalist building. The materials subtlety adds to the design aesthetic.

Another welcome breakthrough in acoustic control is electronic sound masking. Here is how it works. Ironically, a library that is too quiet will feel like a noisy library because every sound, however slight, is so easy to hear.

A “noisier” library, one benefiting from the steady, low-level background hum of the building’s mechanical system, will seem quieter because the background sound masks the otherwise-distracting sneezes and activity noises. Mechanical background noise historically provided a useful source of sound masking in these spaces. Today, mechanical systems are more efficient and therefore much quieter. This is ideal for teaching spaces and conference rooms, but in the open plan, the absence of that white noise hum leads to an unintended consequence — a nosier library experience.

This is why an increasing number of libraries judiciously employ electronic sound masking systems to improve our freedom from distraction. Initially used in workplace design, this technology is now in place at schools, universities, and municipal libraries. In addition to its unobtrusive masking of sounds, these electronic systems do not require much power to run. Sound masking a large section of a library requires the energy needed for a single light bulb.

Summary

Library renovation projects present a distinct opportunity to expand the library’s role in visible and dramatic ways. By creating a thoughtful plan for locating the right neighborhood for each desired activity and designing a sound separation strategy for each, the reimagined space will become a hub for learning and community building while preserving the character of a beloved library experience.