The Virtual Learning Playground demonstrates key takeaways and spatial re-set strategies to enhance human connection, wellbeing, and resilience. Readers are invited to explore this virtual space through the link provided at the end of the article and are encouraged to take these strategies and fold them into their respective on site, or remote learning environments or planned pedagogical experiences in order to expand access to restorative learning environments.

The purpose of the Learning Playground and its associated ongoing research study is to explore the extent to which adaptable translations of biophilic design strategies could be employed in virtual and physical learning environments, regardless of resource abundance or scarcity. Future study will examine insights and takeaways from learners, caregivers, and educators regarding how elements of physical environments, where remote learning occurred, might influence future on-site learning environments.

Provocations:

- How might routine disruption influence the future of learning spaces, experiences? How has COVID-19 influenced routine disruption as part of the learning day?

- How might restorative environments and experiences generated through biophilic design strategies be made more accessible to learners regardless of their access to real nature?

- How might interwoven technologies, like VR/AR play a role in enhancing sense of belonging, and connecting learners to restorative environments?

- What are ways students and educators could adapt their remote-learning environments to capitalize on the benefits of biophilia?

Biophilic Design and Restorative Environments | Background Evidence

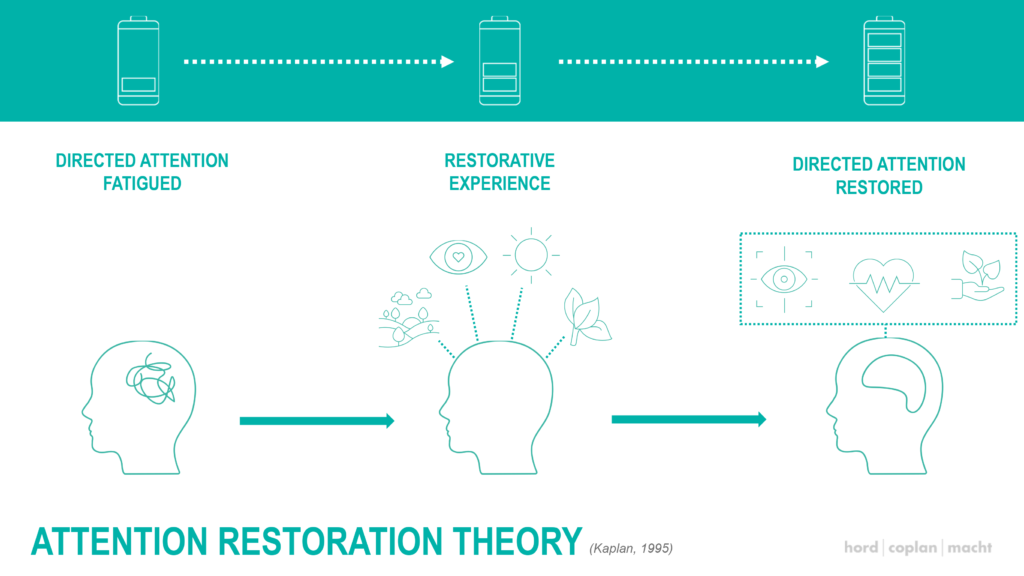

Mounting evidence has documented the link between human health benefits and nature connectedness. Researchers have made more recent connections between simulated, nature-informed patterns and human stress reduction, enhanced cognitive performance, emotion, mood, and visual preference (Browning, et al, 2014; Determan, et. al.). Findings linking human health benefits with exposure to simulated nature, could serve to expand access to restorative environments for learners and educators who may have a perceived or actual barrier to access due to their lack of proximity to real nature. A link exists between research proving the restorative benefits of soft fascination and its inherent tie to human visual preference for biomorphic forms and visual patterns (Kaplan, 1995; Albright, 2015). Research suggests that certain patterns frequently found in the world around us, especially curvilinear features of the built environment please us.

We hypothesize that one reason for this pleasure is the ease by which they are detected and structurally understood by a nervous system that evolved in the presence of such patterns (Albright, 2015). Easy detection of such patterns allows for visual targets of soft fascination to employ our effortless, involuntary attention, rather than using up our limited cache of voluntary attentional capacity, instead allowing that resource to be dedicated towards tasks that require deeper focus and willful, directed attention (Gombrich, 1984; Kaplan, 1995, Albright, 2015). Sensory environments that build on the pleasing patterns found in nature, could serve students and educators by supporting attention restoration, enabling cognitive functions to be replenished in an effort for students to bounce back from fatigue and use their rejuvenated ability to focus on other directed tasks that enhance and facilitate improved learning outcomes and well-being. As studies have demonstrated an affiliation between nature connectedness as a metric for subjective well-being, sense of belonging and human connection have also been utilized as barometers for subjective well-being.

Digital Belongings and Social Cohesion

The Learning playground interweaves technology into the restorative learning environment to probe the potential role of technology in helping to connect both synchronous and asynchronous learners to feelings of belonging, despite potential physical distance. Digital “Belonging” has been defined as relating to conceptions of ‘home’, not home as a fixed entity but rather ‘feeling at home’…an ongoing project of establishing familiarity, security and connectedness (Yuval-Davis, 2011; Marlowe, et. al, 2016). Few studies have explored whether the increased use of technology can enhance social cohesion through meaningful interaction despite physical distance. Initial studies that have explored this concept, independent from spatial implications, suggest that digital environments augmented participant’s physical relationships with people and made possible relationships that were constrained by geographical distance (Marlowe, 2015; p8). This acknowledgement suggests digital technologies can serve to enhance belonging and could be further examined in future studies, within the context of co-located physical and digital spaces for learning and interaction (Marlowe, 2015; p2).

Spaces within the Virtual Learning playground, such as the VR/AR Lounge and the Virtual Grove, support this concept further by suggesting that learning space design include space to build connection between both proximate, and physically distant class cohort participants. These digital platforms exist both in and out of the classroom, and inclusion and cohesion can be amplified by digital interactions, particularly with younger generations. The Learning Playground starts to define physical space that can be quickly adapted to highlight the digital realm, to create space for most learning and activity to happen behind a screen, given that studies suggest benefits are not undermined by this new format. Digital tools such as VR headsets or AR interactions with tablets or smartphones, can allow for shared proximate and distant experiences, and enhance learning by bringing learning and connection occurring outside of the classroom back into the classroom.

Expanding Access to Restorative Environments

Benefits of restorative environments and social cohesion can be reached in both local and digital interventions. In the Learning Playground, the Virtual Grove shows adaptable spatial methods to achieve this by creating a refuge-like space where a student can watch videos or listen to sounds of nature. A lowered overhead ceiling plane, and visual connections to nature scenes with posters or screens can trigger the replenishment that comes from soft fascination and immersion. This type of space can be enhanced with technology to allow for distant interventions. Elements from the Virtual Grove can also apply to engaging in shared virtual experiences such as museum tours or playing games together online. These learning opportunities exist, with a caveat that acknowledges potential barriers to access. Remote access is the biggest barrier for VR/AR, as a headset or smartphone is required and can isolate students who do not have access to these tools. For in-person learning, a barrier to access could be a school district’s inability to supply tools, or resources for educators to gain familiarity with using digital or VR/AR tools as a teaching tool.

Thank you to our partners, Smith System and Steelcase, for their collaboration on the Virtual Learning Playground. The Learning Playground and its additional resources can be found at: https://vr.yulio.com/yhLaubEr2Y

We invite those interested in participating in the ongoing research efforts, or in engaging in research findings pertaining to this topic, to please reach out to vcaruolo@hcm2.com.

References:

Albright, T. D. (2015). Neuroscience for architecture. In S. Robinson & J. Pallasmaa (Eds.), Mind in architecture: Neuroscience, embodiment and the future of design, 197-217. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Browning, W., Ryan, C., & Clancy, J. (1970, January 01). [Pdf] 14 patterns of biophilic design: Improving health and well-being in the built environment: Semantic scholar. Retrieved March 19, 2021, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/14-Patterns-of-Biophilic-Design%3A-Improving-Health-Browning-Ryan/46451d655352680ebbae33965e43d93b1cacfee3

Determan, J., Akers, M. A., Albright, T., Browning, B., Martin-Dunlop, C., Archibald, P., & Caruolo, V. (2019). The impact of biophilic learning spaces on student success. Retrieved from https://www.brikbase.org/content/impact-biophilic-learning-spaces-studentsuccess.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182

Gombrich, E. H. (1984). The Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art. NY: Cornell University Press.

Marlowe, J. M., Bartley, A., & Collins, F. (2016). Digital belongings: The Intersections of Social Cohesion, Connectivity and Digital Media. Ethnicities, 17(1), 85-102. doi:10.1177/1468796816654174, 5

Yuval-Davis, N. (2011). The politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations. doi:10.4135/9781446251041, 10