It may seem like common sense to assume that comfortable temperatures, abundant natural light, and a welcoming civic presence would benefit a school’s occupants. But Perkins Eastman has backed that assumption with a decade of research, recently culminating in a multiyear study with Drexel University. “Addressing a Multi-Billion Dollar Challenge” reinforces the firm’s previous work with larger samples that make it statistically significant. The increasingly indisputable message is that the quality of a school’s structure, layout, interiors, and landscape — even its standing in the community — has a material impact on the performance and well-being of those who work, teach, and learn there.

The study’s implications for school districts across the country are far-reaching: nearly 50 million children were enrolled in public schools in 2021, and the average age of public schools in the United States is 49 years, based on the most recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics, yet the nationwide shortfall in maintenance, operations, and capital expenditures at those schools has reached $85 billion annually, according to the “2021 State of Our Schools” report published by the 21st Century School Fund, International WELL Building Institute, and National Council on School Facilities.

The Perkins Eastman-Drexel study, published earlier this year, was funded in part by the Latrobe Prize, a biennial $100,000 grant from the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows that supports “research leading to significant advances in the architecture profession.” J+J Flooring provided an additional $30,000 as part of its continued support of Perkins Eastman’s research. Testing indoor environmental quality, a school’s “educational adequacy,” and its community connections, the study compared conditions at 28 modernized and non-modernized schools across District of Columbia and Baltimore City public schools. The K-12 Education practice has since put the assessment tools created for this study to effective use in other school districts. “They are significantly enhancing our strategic planning capabilities,” says Perkins Eastman Principal Sean O’Donnell, who leads the practice. “With the addition of these tools, we can help clients really understand the performance and the quality of their learning environments.”

Statistical Foundation

O’Donnell and his team knew they were onto something when the new building they designed for the historic Paul Laurence Dunbar Senior High School opened in 2013, replacing the deteriorated facility it previously occupied in Washington, DC. In achieving its LEED Platinum certification two years later, Dunbar became the highest-scoring LEED for Schools project in the world. Student test scores increased faster than they did at any other school in the district the following year, and graduation rates rose. (The rates have continued upward, from 60.3 percent the year before the new building opened to 83.4 percent in 2022.)

The increasingly indisputable message is that the quality of a school’s structure, layout, interiors, and landscape — even its standing in the community — has a material impact on the performance and well-being of those who work, teach, and learn there.

Based on those early numbers, “Sean started to say, ‘I think this is proof that high-performance, sustainable projects contribute to better educational outcomes,’” notes Perkins Eastman Associate Principal and Director of Sustainability Heather Jauregui. That’s when they asked Senior Associate and Design Research Director Emily Chmielewski to begin a regular practice of performing pre- and post-occupancy evaluations on new schools and renovations. Her work led to “Investing in Our Future,” a 2018 white paper that compared the indoor environmental quality — thermal comfort, daylight, acoustics, and air quality — at nine modernized and non-modernized schools in the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) system. That study found a statistically significant correlation between a modernized school’s indoor environmental quality and its occupants’ improved satisfaction and well-being. Perkins Eastman Principal Patrick Davis, who at the time was the DCPS chief operating officer, presented the results of “Investing in Our Future” to the city. The mayor and city council “fully bought into really trying to understand and acknowledge that the building modernization program at DCPS was having a positive impact,” he says, “and after that, we saw increases in our budgets.”

Opportunity Knocks

O’Donnell acknowledges, however, there were still unanswered questions: “When we conducted the nine-school study, we didn’t focus on the programming of the buildings—do they support contemporary teaching and learning practices, curricula, and pedagogies?” When the AIA College of Fellows opened its submission process for the 2019 Latrobe Prize, the timing inspired O’Donnell, Jauregui, and Chmielewski to expand their line of inquiry. Davis agreed to be a stakeholder representative for the grant application. And by coincidence, O’Donnell had just met Bruce Levine, a Washington, DC-based clinical professor at Drexel’s School of Education and director of its Education Policy Program. One of Levine’s primary research interests is community schools. “I was interested in exploring how the school building itself impacted various stakeholders and, specifically, the community surrounding it. I hadn’t seen much work done around that,” Levine says.

The group’s collective expertise and interests proved a winning combination. The Perkins Eastman-Drexel research collaboration, formalized as the Consortium for Design and Education Outcomes (CDEO), secured the 2019 Latrobe Prize, plus the additional funding from J+J Flooring. Although the pandemic delayed some of the fieldwork and altered the collaborators’ approach to some degree, the study showed statistically significant results that confirmed and expanded upon the earlier research. “Now we have the data to support all the beliefs and approaches Perkins Eastman has been preaching for years,” says Associate Principal Karen Gioconda, the study’s project manager.

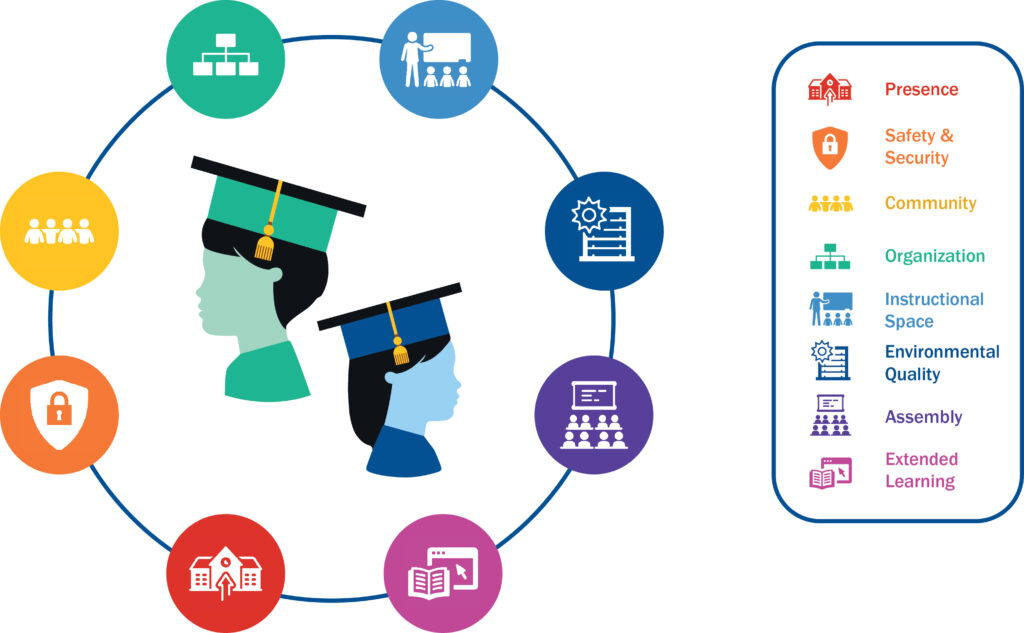

The study’s findings indicate that modernized schools outperform non-modernized schools in several areas, including indoor environmental quality (echoing the smaller 2018 study); first impressions on arrival; better safety measures and strategies; and “enhanced learning ambiance.” Evidence also emerged, in line with those first indications at Dunbar, that modernization correlated with increases in test scores, graduation rates, and enrollment over time. A modernized school’s strength in the community was harder to quantify due to the pandemic, though early indications were positive and will receive further investigation.

Real-World Applications

Even before the report was completed, Davis was already using the study’s Visual Assessment Tool (VAT) for strategic consulting. Traditional school assessments evaluate building conditions, O’Donnell explains. “While assessing the physical integrity of a building is important, these assessments typically ignore whether the building is actually a supportive place to learn. Is it a good 21st-century school?” The VAT, conducted using a smartphone app, enables users to survey and document conditions such as safety and security, classroom organization, ease of navigation, and indoor and outdoor “ambiance.” The VAT is already in its third generation and in use with multiple clients. “We’re able to show them where they’re deficient in terms of meeting what we identify as a 21st-century learning environment,” Davis says. “It’s opened up a lot of eyes in terms of what a school building could and should be.”

Last November, the Colorado Springs school district awarded $80 million for improvements to Palmer High School, which the VAT showed to be most in need of modernization among its four high schools during a district-wide assessment. “That probably wouldn’t have been done if we didn’t share the VAT data and help the district understand the importance of it,” Davis notes.

Looking Outward

The “Addressing a Multi-Billion Dollar Challenge” researchers were unable to interview as many students, teachers, parents, and community members as they would have liked during the pandemic. But COVID-19 demonstrated that many people relied on their schools for multiple forms of assistance such as meal pickups and social services, Chmielewski says. “In some ways, it was interesting for COVID-19 to happen during this study because the community-connectivity piece of it became so much more valuable—we saw clear examples of how a school serves more than just an educational purpose.”

The CDEO has already embarked on a second, related investigation, examining how a school’s design can make it a better community partner with features such as food distribution, adult General Educational Development classrooms, health clinics, and publicly accessible recreational and meeting facilities. In this respect — not to mention the enduring benefits for students, teachers, staff, parents, and other local stakeholders that modernization has already brought about — Perkins Eastman’s decade of ground-breaking research continues to transform the landscape for public school education and its community-wide influence.